HIV Drug Interaction Checker

How This Works

Select your HIV medication and any other medications you're taking to see potential interactions. This tool is based on the latest guidelines from the Department of Health and Human Services.

When HIV first became a global crisis in the 1980s, a diagnosis often meant a death sentence. Today, thanks to antiretroviral therapy (ART), people living with HIV can expect to live long, healthy lives - if they stay on their meds and avoid resistance. But behind that simple success story lies a complex battle between drugs, viruses, and the human body. Antiretroviral medications don’t just kill HIV; they outsmart it. And when they fail, it’s rarely because the drug is weak. More often, it’s because of interactions with other pills, or because the virus found a way to escape.

How Antiretroviral Drugs Work

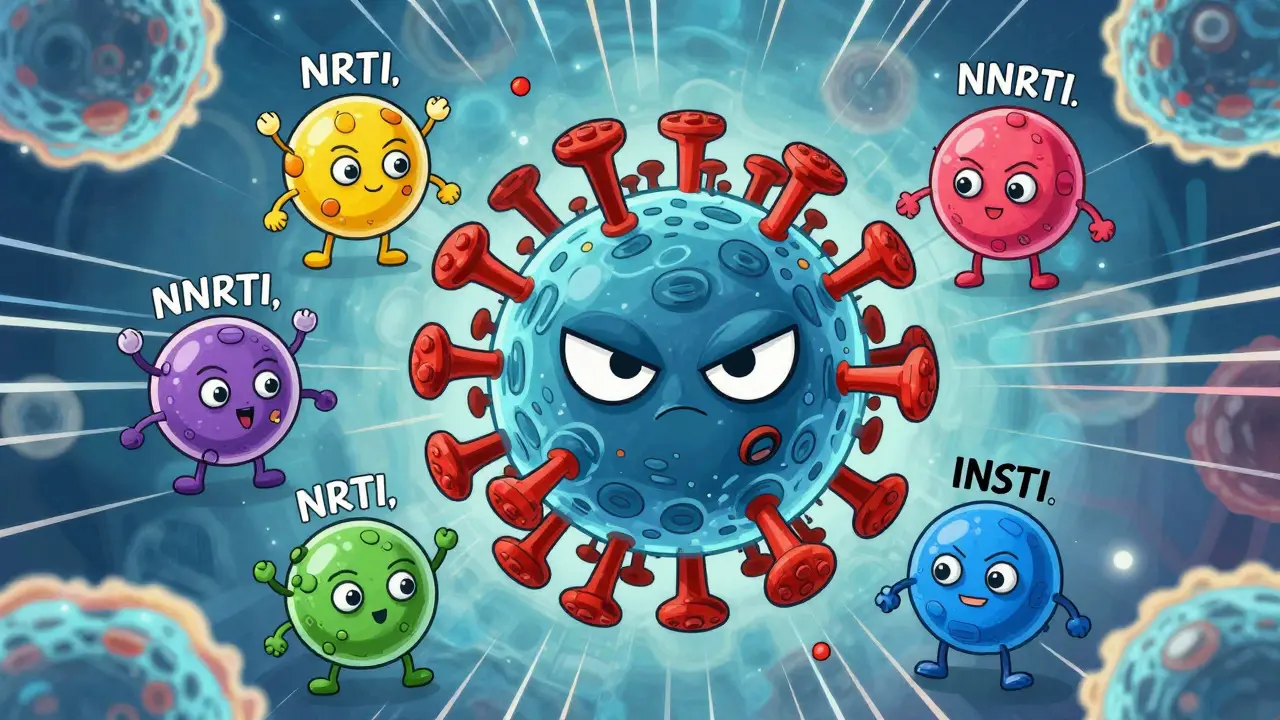

HIV doesn’t just infect cells - it hijacks them to make copies of itself. Antiretroviral drugs block that process at different stages. There are six main classes, each targeting a specific step in the virus’s life cycle. The most common ones used today are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs).NRTIs like tenofovir and emtricitabine act like fake building blocks. When HIV tries to copy its genetic material, it grabs these imposters instead of the real ones, and the replication process stops. INSTIs like dolutegravir and bictegravir prevent the virus from inserting its DNA into human cells - a critical step for long-term infection. These newer drugs are so effective that they’re now the go-to choice for starting treatment. In fact, 78% of new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. in 2024 began with an INSTI-based regimen.

Why the shift? Because they’re tougher for the virus to resist. Older drugs like efavirenz (an NNRTI) could be defeated by a single mutation. Dolutegravir, on the other hand, needs multiple mutations to lose its power. That’s why the Department of Health and Human Services recommends it as a first-line option. The goal isn’t just to lower the viral load - it’s to keep it undetectable for decades.

Why Drug Interactions Are a Silent Threat

Most people with HIV aren’t taking just one pill. They’re often managing high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, or cholesterol. That means 47% of them are on five or more non-HIV medications. And that’s where things get dangerous.Many antiretrovirals are broken down by the same liver enzymes - especially CYP3A4 - that process common drugs like statins, anti-anxiety meds, and even some herbal supplements. Boosted protease inhibitors, for example, can make the levels of simvastatin (a cholesterol drug) spike by over 700%. That’s not just a side effect - it’s a risk of muscle damage, kidney failure, or even death.

Even newer drugs aren’t immune. Doravirine, a newer NNRTI, has fewer interactions than older ones like efavirenz, but it still can’t be mixed with certain seizure medications or St. John’s wort. And while tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) is gentler on the kidneys than its older cousin TDF, it still interacts with some kidney-toxic drugs like aminoglycosides.

One of the biggest hidden dangers? Stopping a drug without knowing the consequences. If someone on a regimen like DELSTRIGO (which includes doravirine and tenofovir) stops taking it suddenly, hepatitis B can flare up - sometimes violently. That’s because the same drug suppresses both HIV and HBV. Discontinuing it without medical supervision can trigger liver failure.

Resistance: When the Virus Adapts

Resistance isn’t magic. It’s evolution. Every time HIV copies itself, it makes mistakes. Most of those mistakes kill the virus. But sometimes, one of those errors lets it survive a drug. If the person misses doses, the drug levels drop just enough to let those resistant strains survive and multiply.Some mutations are well-known. The M184V mutation, for example, makes HIV resistant to lamivudine and emtricitabine - two of the most common NRTIs. But here’s the twist: even though this mutation breaks those drugs, it actually makes the virus weaker and slower to replicate. That’s why some doctors still keep these drugs in the regimen - they’re not useless, just limited.

INSTIs like dolutegravir were supposed to be resistance-proof. But they’re not. A combination of two mutations - R263K and G118R - has already been seen in patients who failed treatment. And now, a new drug called VH-184 is being tested specifically to beat those resistant strains. In early trials, it slashed viral load by 1.8 logs in just weeks. That’s not just promising - it’s a lifeline for people who’ve run out of options.

But resistance isn’t just about treatment failure. It can start before treatment even begins. About 16.7% of newly diagnosed people in the U.S. already carry HIV that’s resistant to at least one drug. That’s why genotype testing at diagnosis is now mandatory. Without it, you might start someone on a drug that won’t work - and waste precious time.

Long-Acting Injectables: The New Frontier

The biggest breakthrough in recent years isn’t a new pill - it’s a shot. Cabenuva, a monthly injection of cabotegravir and rilpivirine, has changed the game for adherence. In clinical trials, 94% of users preferred it to daily pills. No more remembering 30 pills a month. Just two shots every 4 weeks.But there’s a catch. If you miss a shot, the drug levels don’t drop overnight. They linger for weeks - at levels too low to kill the virus, but high enough to train it to resist. That’s why experts warn: injectables aren’t easier. They’re riskier if you’re inconsistent.

Even more advanced is lenacapavir, a twice-yearly injection approved in 2022 for multi-drug resistant HIV. Now, in 2025, the WHO recommends it for prevention too - a game-changer for people who struggle with daily PrEP. But it’s expensive, and access is limited. In rural clinics, getting this drug can mean waiting months.

Who’s at Risk for Resistance?

It’s not just about skipping pills. Certain groups face higher risks. People with untreated hepatitis B or C are more likely to develop resistance because their livers are already stressed. Those on older regimens like efavirenz - which causes insomnia, dizziness, and depression - often stop because of side effects, not because the drug failed. That’s why switching to dolutegravir or bictegravir reduces resistance rates from 3.2% to just 0.4% over two years.And then there’s the silent group: people on PrEP. Truvada and Descovy are highly effective - but not perfect. There have been documented cases of people contracting HIV despite daily use. Genotype tests show the M184V mutation was already present. That means the virus was resistant before it even took hold. It’s rare - but it happens.

What You Need to Do

If you’re on ART, here’s what matters:- Never skip a dose - even if you feel fine.

- Tell your doctor every medication you take - including vitamins, supplements, and over-the-counter painkillers.

- Get a resistance test at diagnosis and again if your viral load rises.

- Ask about long-acting options if daily pills are a struggle.

- If you’re on tenofovir, get bone density and kidney tests yearly.

- If you’re on abacavir, make sure you were tested for HLA-B*5701 before starting.

The tools to beat HIV are better than ever. But they only work if you use them right. The virus doesn’t care about your intentions. It only responds to the levels in your blood. And if those levels dip - even for a day - it starts adapting.

What’s Next?

The future of HIV treatment isn’t just about more drugs. It’s about smarter ones. ViiV Healthcare is testing a six-month injectable version of VH-184. Gilead is working on a 12-month implant. And researchers are using AI to predict which mutations will emerge next - so we can design drugs before resistance even appears.But none of that matters if we don’t fix the gaps. In sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 30% of new HIV cases involve drug-resistant strains. In rural U.S. clinics, 63% of providers can’t get resistance tests within 30 days. And in many places, the cost of newer drugs is still out of reach.

HIV is no longer a death sentence. But it’s still a battle. And winning it means more than just taking a pill. It means understanding how the drugs work, how they interact, and how the virus fights back.

Can you develop resistance to HIV meds even if you take them perfectly?

It’s rare, but possible. If you’re infected with a strain of HIV that’s already resistant - even before you start treatment - the drugs won’t work from day one. That’s why resistance testing at diagnosis is critical. Also, some drugs have lower resistance barriers. For example, efavirenz can fail with just one mutation, while dolutegravir needs several. So even perfect adherence won’t help if the virus was resistant before you began.

Why do some HIV drugs cause weight gain?

Weight gain is most common with INSTIs like dolutegravir and bictegravir. The exact reason isn’t fully understood, but studies suggest it may involve changes in how fat cells store energy or how the body processes insulin. It’s not universal - about 10-15% of users gain significant weight - but it’s one reason some people switch regimens. Abacavir and tenofovir-based drugs tend to cause less weight gain.

Is it safe to take HIV meds with alcohol or marijuana?

Moderate alcohol use is generally okay with most HIV drugs, but heavy drinking can damage your liver - especially if you’re on boosted protease inhibitors or have hepatitis C. Marijuana doesn’t directly interact with antiretrovirals, but it can worsen side effects like dizziness or nausea. More importantly, if using cannabis leads to missed doses, it increases resistance risk. The real danger isn’t the chemical interaction - it’s the impact on adherence.

What happens if you miss a dose of a long-acting injection?

Missing a single injection isn’t an emergency, but it’s risky. Unlike daily pills, injectables like Cabenuva or lenacapavir release drug slowly over weeks. If you’re late by more than a week, drug levels can drop into a range that doesn’t fully suppress the virus - enough to let resistant strains grow. If you miss a shot, contact your provider immediately. They may need to restart you on daily pills until you can get back on schedule.

Can you switch from one HIV regimen to another safely?

Yes, but only under medical supervision. Switching too quickly or without testing can trigger resistance. For example, switching from a regimen containing tenofovir to one with abacavir requires an HLA-B*5701 test first - otherwise, you risk a life-threatening allergic reaction. Even switching between INSTIs can be dangerous if you have existing resistance mutations. Always get a resistance test before changing regimens.

Are generic HIV drugs as good as brand-name ones?

For most NRTIs like tenofovir and lamivudine, yes - generics are just as effective and safe. The FDA requires them to meet the same standards as brand-name drugs. But for newer drugs like INSTIs, generics aren’t available yet. And in treatment-experienced patients, even small differences in absorption can matter. If you’re stable on a brand-name drug, switching to a generic isn’t always necessary - especially if cost isn’t a barrier.

How often should you get tested for drug resistance?

At diagnosis - always. Then again if your viral load rises above 200 copies/mL after being suppressed. Some experts recommend testing every 1-2 years if you’re stable, but guidelines vary. The key is: don’t wait for symptoms. A rising viral load is the only clear sign resistance is developing. Routine testing every few years isn’t recommended unless there’s a reason to suspect failure.

Can HIV resistance be reversed?

Not directly. Once a mutation is in the virus’s genetic code, it stays there. But sometimes, resistant strains become less fit over time. For example, the M184V mutation makes HIV less able to replicate - so if you stop the drug that caused it, the wild-type (non-resistant) virus may bounce back. That’s why some doctors use a "drug holiday" strategy before switching - but only under strict supervision. Never stop meds on your own.

Lance Nickie

January 13, 2026 AT 07:25INSTIs are just fancy placebos until you factor in access.

Priyanka Kumari

January 13, 2026 AT 14:33Really glad this post breaks down the real-world stuff - like how missing a shot with Cabenuva is way riskier than missing a pill. So many people think long-acting = easy, but it’s actually a high-stakes game of timing. Kudos for highlighting adherence traps.

Milla Masliy

January 14, 2026 AT 07:09I’ve seen this in my work in rural clinics - patients on tenofovir get kidney issues, but no one tells them to get annual tests. We’re treating HIV like it’s a cold. It’s not. It’s a chronic condition that needs monitoring, not just pills. Also, why is it still so hard to get genotype testing in 2025? We have apps for everything else.

And yes, weight gain with dolutegravir? Real. My cousin gained 30 lbs in 6 months. No change in diet. No change in activity. Just switched meds. Doctors shrugged. That’s not medical care - that’s negligence.

Adam Vella

January 15, 2026 AT 09:26One must consider the epistemological framework of viral resistance - it is not merely a biological phenomenon, but a metaphysical confrontation between human intentionality and the indifferent machinations of evolutionary entropy. The virus, in its relentless replication, embodies the Nietzschean will to power - a force that does not seek to destroy, but to transcend the constraints imposed by pharmacological hegemony.

Thus, when we prescribe dolutegravir, we are not merely administering a drug; we are attempting to impose a Cartesian order upon a chaotic, self-replicating system that has no allegiance to human morality, nor to clinical guidelines. Resistance, then, is not failure - it is evolution’s quiet rebellion.

And yet, we persist. We engineer drugs with ever-lower resistance barriers, as if the universe owes us compliance. But the virus does not care for our algorithms, our AI predictions, our six-month injectables. It only knows replication. And in that, it is the true philosopher.

Perhaps the real breakthrough is not in the lab, but in our humility. To accept that we are not the masters of this virus - merely its temporary, flawed hosts.

Avneet Singh

January 15, 2026 AT 11:28Let’s be honest - the entire ART paradigm is a corporate construct designed to monetize chronicity. INSTIs? Patent-protected. Cabenuva? $30k/year. Meanwhile, generic NRTIs have been around since 2005 and work just fine for 80% of people. Why are we pushing expensive, high-risk injectables on folks who can’t even afford a monthly bus pass to the clinic? It’s not medicine - it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

And don’t get me started on ‘genotype testing at diagnosis.’ In India, we wait six weeks for results. By then, the patient’s viral load is already climbing. So yes, we start them on dolutegravir - because what else can we do? But calling it ‘standard of care’ is a euphemism for ‘we’re winging it.’

Lethabo Phalafala

January 16, 2026 AT 13:58I lost my brother to HIV in 2008. He missed doses because he was depressed and couldn’t afford the bus fare to the clinic. No one told him about drug interactions - he was taking ibuprofen for his back pain and didn’t know it could tank his kidney function. He didn’t die from HIV. He died from neglect.

This post? This is the kind of info that saves lives. Not the fancy injectables. Not the AI predictions. But the simple stuff: ‘Tell your doctor every pill you take.’ ‘Get tested for HLA-B*5701.’ ‘Don’t stop your meds because you’re tired.’

I wish someone had given me this when I was 19. I wish they’d given it to him. Please - if you’re reading this and you’re on ART - don’t wait for a crisis. Talk to your provider. Write down every medication. Bring your pill bottles. Don’t be ashamed. Your life isn’t a statistic. It’s a story. And you’re still writing it.

Damario Brown

January 17, 2026 AT 01:15ok but like… why are we even still talking about this? Like i know i’m on truvada and i take it and i’m fine. why do i need to know about cyp3a4 or r263k mutations? i just wanna not die. also i took a tylenol last week and my liver feels fine so idk why everyone’s freaking out. also why is everyone so obsessed with ‘resistance’? like if i miss a pill once, does the virus start doing a victory dance? lol. also why are we using ‘logs’ like we’re in a sci-fi movie. it’s just pills. why is this so complicated?

Clay .Haeber

January 17, 2026 AT 20:53Oh wow. A 10-page essay on HIV meds and not a single mention of how Big Pharma is literally *profiting* from the myth of ‘perfect adherence.’ You know what’s more effective than dolutegravir? A guaranteed paycheck, a stable home, and a therapist who doesn’t judge you for using weed. But nah - let’s blame the patient for missing a dose while their landlord raises the rent 40%. Brilliant.

Also, ‘long-acting injectables are riskier if inconsistent’? Tell that to the guy who’s working two jobs and can’t take a day off to get his shot. That’s not ‘riskier’ - that’s systemic violence wrapped in a syringe.

And don’t even get me started on ‘genotype testing at diagnosis.’ Yeah, sure. In Manhattan. In rural Alabama? They’re still using 2012 protocols and calling it ‘standard care.’ This post reads like a Gilead investor pitch disguised as public health.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 19, 2026 AT 11:23man i just wanna say… this is wild. like, we’re living in the future and we still gotta fight for basic access. i got my cabenuva shot last month and honestly? i’m not gonna lie - i cried. not because i’m weak - because for the first time in 12 years, i didn’t have to think about pills every damn morning. but then i saw the bill. $2,800. and i’m like… how? how is this even possible? we’re not even talking about curing anything. we’re talking about *managing* a disease like it’s a subscription service. 😔💊

also - st john’s wort? yeah i tried that ‘natural remedy’ last year. my viral load went up. my doctor didn’t even ask. i had to bring it up. so yeah… tell your doc everything. even if it’s ‘just’ herbal tea. it matters. 💪

Trevor Whipple

January 20, 2026 AT 17:45u guys are overcomplicating this. if u take ur meds every day u fine. if u dont, u get resistance. its that simple. stop making it a philosophy thing or a class thing. its just pills. if u cant handle 1 pill a day, then u shouldnt be on it. end of story. also why are we talking about weight gain like its a crisis? i gained 15lbs and now i look better. who cares? stop being dramatic.

sam abas

January 21, 2026 AT 10:23Let’s be real - the entire narrative around INSTIs being ‘resistance-proof’ is a myth peddled by pharmaceutical marketing departments. The R263K/G118R combo was documented in 2021 in a small cohort in Kenya, yet it’s barely mentioned in U.S. guidelines. Why? Because the narrative is ‘new drugs = better.’ But what if ‘better’ is just more expensive and less accessible? And let’s not forget - resistance isn’t just about mutations. It’s about supply chains. In sub-Saharan Africa, 37% of clinics report drug stockouts. So even if you take your meds perfectly, if the pharmacy ran out of dolutegravir last week and gave you efavirenz instead… guess what? Resistance happens. Not because you failed. Because the system did.

And the ‘long-acting injectables are easier’ claim? That’s pure performative optimism. It’s like saying, ‘Hey, instead of driving to the store every day, just get a car that runs on magic.’ Cool. But what if you live 50 miles from the clinic? What if the bus doesn’t run on Tuesdays? What if your job doesn’t let you take a day off? The tech is brilliant. The infrastructure? Broken. And pretending otherwise is unethical.

Also - why is no one talking about the fact that 16.7% of newly diagnosed people already have resistance? That means we’re starting people on regimens that won’t work - and we’re calling it ‘first-line.’ That’s not medicine. That’s gambling with someone’s life. And the fact that we’re not screaming about this is the real crisis.

John Pope

January 21, 2026 AT 19:19THE VIRUS ISN’T THE ENEMY - THE SYSTEM IS.

They give you a pill. Then they charge you $1,200 for it. Then they tell you it’s ‘lifesaving’ - but don’t offer you housing, food, or mental health care. Then they pat themselves on the back for ‘reducing resistance rates’ while people in rural Georgia wait 90 days for a resistance test.

And let’s talk about ‘perfect adherence.’ Who gets to be perfect? The billionaire in San Francisco? Or the single mom working three shifts, sleeping in her car, and taking ten pills a day with no running water to wash them down?

They call it ‘treatment.’ I call it trauma with a prescription label.

And now they want us to inject drugs every month? Great. Let’s just make it harder. Let’s make the clinic a 6-hour bus ride away. Let’s make the shot cost more than rent. Let’s make the patient feel guilty when they can’t show up. Brilliant. We’re not curing HIV. We’re turning it into a moral test.

And the AI predicting mutations? Cute. But AI doesn’t fix broken clinics. AI doesn’t pay for PrEP. AI doesn’t give people food stamps. So don’t talk to me about ‘the future’ when the present is collapsing.

Nelly Oruko

January 23, 2026 AT 11:56While the scientific underpinnings of antiretroviral resistance are well-documented, the ethical imperative to ensure equitable access to next-generation therapeutics remains grossly unaddressed in contemporary discourse. The conflation of pharmacological efficacy with social determinants of health constitutes a critical epistemological blind spot - one that risks pathologizing socioeconomic disadvantage as non-adherence. Furthermore, the proliferation of long-acting injectables, while clinically advantageous, exacerbates structural disparities in care delivery, particularly in low-resource settings where cold-chain logistics and provider training remain inadequate. A paradigm shift from biomedical reductionism to holistic, patient-centered care is not merely advisable - it is a moral necessity.

Clay .Haeber

January 24, 2026 AT 14:41Oh wow, Nelly just dropped the academic bomb. ‘Epistemological blind spot’? Cute. Meanwhile, my cousin in Mississippi still can’t get a resistance test because the nearest lab is 120 miles away and Medicaid won’t cover the ride. So yeah - your fancy words don’t fix broken buses, Nelly. Keep your ‘holistic paradigm’ and give us a damn van.