When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But what if the batch of generic pills you’re holding isn’t even close to the batch used in the bioequivalence study? This isn’t a hypothetical concern-it’s a real, documented flaw in how generic drugs are approved. The current system assumes that if one batch of a generic drug matches one batch of the brand drug in a small study, then all future batches will behave the same. But data shows that’s not true. Batch-to-batch variability can account for 40% to 70% of the total error in bioequivalence studies, meaning the results you see in the lab might have nothing to do with what ends up in your medicine cabinet.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

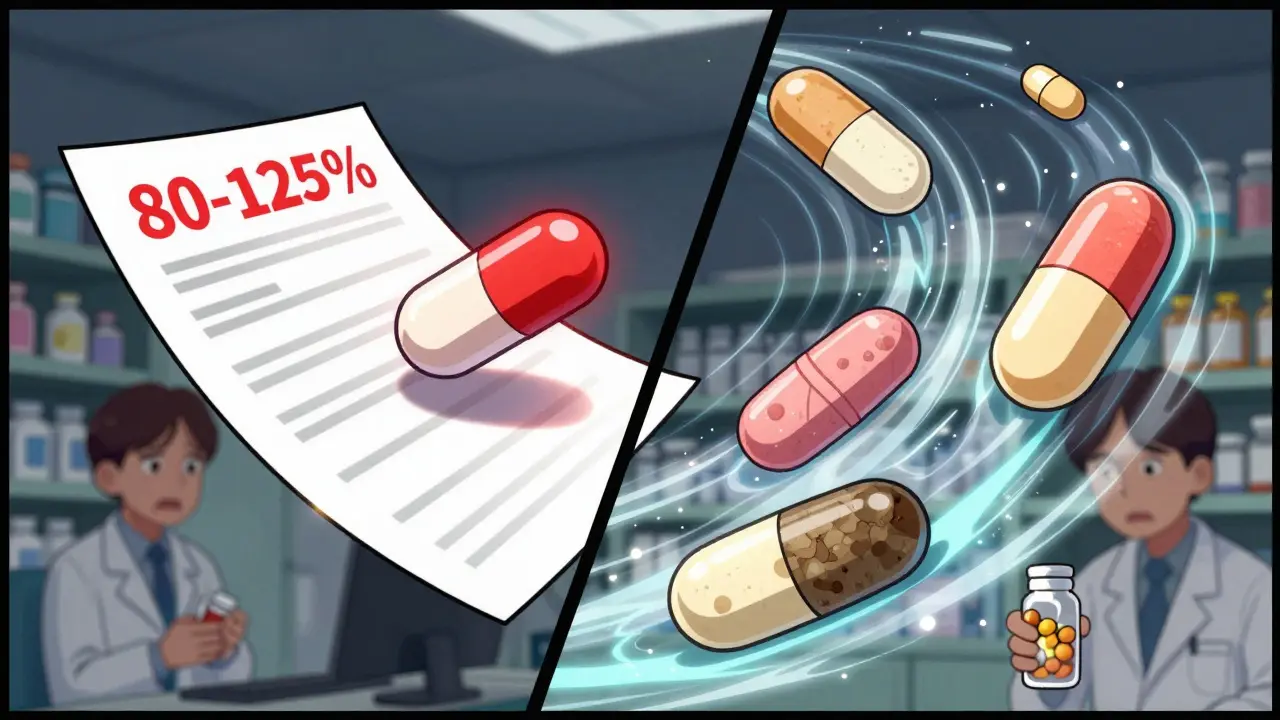

Bioequivalence is the standard used by regulators like the FDA and EMA to approve generic drugs without running expensive clinical trials. The idea is simple: if the generic delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed as the brand, it’s considered equivalent. The test? Measure two key numbers-AUC (total drug exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration)-and check if the ratio between the generic and brand falls between 80% and 125%. That’s it. If it’s inside that range, the drug gets approved. But here’s the problem: this 80-125% rule was designed for a world where every batch of a drug was identical. It wasn’t built for reality. In practice, even the same brand-name drug made in different factories, on different days, or with slightly different ingredients can vary. A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that when multiple batches of the same brand drug were tested, their AUC and Cmax values differed enough to push some results outside the 80-125% range. If the brand itself doesn’t stay consistent, how can we expect a generic to match it perfectly every time?Why Single-Batch Testing Is Broken

Right now, the standard bioequivalence study uses just one batch of the generic and one batch of the brand. That’s it. The study might involve 24 people, each taking both versions in a crossover design. The results are averaged, a confidence interval is calculated, and if it fits inside 80-125%, the drug is approved. But this approach ignores the biggest source of variability: the manufacturing process itself. A 2016 study showed that between-batch differences can make up nearly two-thirds of the total error in these studies. That means the difference you see between the generic and brand might not be because the generic is worse-it might just be because the brand batch used in the study happened to be unusually potent or weak. Imagine testing two cars for fuel efficiency. You take one 2023 Honda Civic from the Toronto plant and compare it to one 2023 Honda Civic from the Ohio plant. They’re the same model, same year, same engine. But if the Ohio car gets 32 mpg and the Toronto car gets 28 mpg, is one broken? Or is this just normal variation in production? Now imagine you only tested one car from each plant. You’d conclude they’re not equivalent. But if you tested five from each, you’d see the average is the same. That’s what’s happening with drugs. Single-batch testing is like judging a whole product line based on one random sample.The Hidden Risk: False Equivalence

The biggest danger isn’t that a bad generic gets approved. It’s that a good one gets rejected. When batch variability is high and not accounted for, the confidence intervals in bioequivalence studies get artificially wide. This makes it harder for even perfectly good generics to meet the 80-125% rule. A 2019 presentation by Dr. Robert Lionberger, former head of the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs, called this “one of the most significant statistical oversights in modern bioequivalence.” He warned that this leads to false negatives-good drugs being turned away-while also increasing the risk of false positives, where a poorly made generic slips through because the brand batch used in testing happened to be unusually weak. This isn’t theoretical. The FDA reported a 22% increase in bioequivalence-related deficiencies in generic drug applications between 2019 and 2022. Many of these were tied to insufficient batch characterization. In other words, companies weren’t proving their product was consistent across production runs. Regulators are catching on. But the system hasn’t caught up.

What’s Being Done: The Rise of Multi-Batch Testing

The solution isn’t to make the 80-125% rule stricter. It’s to change how we test. A new approach called Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE) is gaining traction. Instead of comparing a single generic batch to a single brand batch, BBE compares the average performance of multiple batches of the generic to the natural variation seen in multiple batches of the brand. If the generic’s average performance falls within the range of the brand’s own batch differences, it’s considered equivalent. This method was proposed in 2020 and has been validated in simulations. When researchers tested with just three reference batches, the success rate of correctly identifying equivalent products was around 65%. With six batches, it jumped to over 85%. That’s a huge improvement. The EMA now recommends testing at least three reference batches and two test batches for complex products like inhalers and nasal sprays. The FDA’s 2022 guidance on nasal sprays requires applicants to provide data on at least three production-scale batches of both test and reference products. And in June 2023, the FDA released a draft guidance titled Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies-a clear signal that the old single-batch model is being phased out.Who’s Affected and How

This shift matters most for complex drug products. Nasal sprays, inhalers, topical creams, and injectables are especially sensitive to small changes in manufacturing. A tiny difference in particle size, viscosity, or excipient distribution can change how the drug is absorbed. For these products, batch variability isn’t noise-it’s the signal. But even simple oral tablets aren’t immune. A 2021 study in Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy found that batch variability in extended-release tablets could alter release profiles enough to impact therapeutic outcomes. The same applies to generics made with new manufacturing techniques, like continuous production, which the ICH is now addressing in its draft Q13 guideline. For patients, this means better, more consistent drugs. For manufacturers, it means higher upfront costs. Testing multiple batches requires more resources, more volunteers, and more complex statistical analysis. But it also means fewer rejections, fewer delays, and more reliable products on the shelf.

Jake Moore

January 17, 2026 AT 12:36Let me break this down real simple: if the brand drug itself varies by 20% between batches, then demanding a generic match it perfectly is like demanding a copy of a blurry photo be sharper than the original. Multi-batch testing isn’t just smarter-it’s the only scientifically honest way forward. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance is long overdue, and kudos to the EMA for leading the charge. This isn’t about cost-it’s about patient safety.

christian Espinola

January 18, 2026 AT 21:39They’ve been lying to us for decades. One batch. Twenty-four people. That’s it? They’re not testing drugs-they’re playing roulette with our health. I’ve seen people go from stable to crashing after switching generics. Coincidence? Or just the system ignoring the fact that pills aren’t M&Ms? Wake up, people. This is Big Pharma’s backdoor to keep generics cheap and dangerous.

Tyler Myers

January 19, 2026 AT 08:48Look. I get it. The 80-125% rule was a shortcut. But let’s not pretend this is some massive conspiracy. The FDA doesn’t approve drugs based on one batch because they’re lazy-they do it because statistically, it’s sufficient for simple oral solids. The real issue? Complex formulations. Inhalers, injectables, topical creams-those need multi-batch testing. Tablets? Probably fine. Stop overgeneralizing. And yes, I’ve read the 2016 CPT paper. I know what I’m talking about.

Ryan Otto

January 20, 2026 AT 09:11It’s not merely a statistical oversight-it’s a systemic collapse of regulatory epistemology. The very premise of bioequivalence assumes linearity and homogeneity in pharmacokinetics, which is a gross misrepresentation of biological systems. The EMA’s three-batch recommendation is a minimal concession; true scientific rigor would demand longitudinal, population-based pharmacokinetic modeling across manufacturing sites. The current paradigm is not merely outdated-it is epistemologically bankrupt.

Praseetha Pn

January 20, 2026 AT 20:35Oh, so now we’re supposed to trust the FDA? LOL. They approved OxyContin and let Big Pharma turn addiction into a business model. Now they want us to believe they’re suddenly ethical about generics? Please. This whole system is rigged. One batch? Ha. They’re not testing for safety-they’re testing for profit. And guess what? You’re paying for it-with your life. I’ve seen friends die because their ‘equivalent’ meds didn’t work. This isn’t science. It’s corporate greed in a lab coat.

Max Sinclair

January 21, 2026 AT 10:35Really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years, and I’ve had patients tell me their generic stopped working after a switch-even though the label said ‘same active ingredient.’ This post nails why: we’re not looking at the whole picture. Multi-batch testing feels like common sense. If the brand varies, the generic shouldn’t have to hit a magic number-it should just stay in the same ballpark. Hope this becomes standard soon.

Naomi Keyes

January 22, 2026 AT 14:01While I appreciate the emphasis on batch variability, the article’s conflation of ‘manufacturing variance’ with ‘clinical inequivalence’ is misleading. Statistical confidence intervals are not arbitrary-they are calibrated to account for biological variability, intra-individual differences, and assay error. To demand multi-batch testing for all generics is to ignore cost-benefit analysis. For immediate-release tablets, the current paradigm remains scientifically valid. The EMA’s guidance for complex products is appropriate-but extending it universally? Unnecessary. And frankly, alarmist.

Robert Davis

January 24, 2026 AT 06:06You know what’s wild? The same people who scream about ‘generic drugs being fake’ are the ones who don’t even know how to read a prescription label. But here’s the thing-I’ve worked in a pharmacy for 15 years. I’ve seen generics fail. I’ve seen them work better than the brand. It’s not about the system being broken. It’s about the system being oversimplified. The real villains? The pharmacies that switch brands without telling patients. And the doctors who don’t track outcomes. This isn’t a regulatory failure-it’s a communication failure. And before you all start yelling about conspiracies… maybe check your own pharmacy’s substitution log first.