When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in bioavailability studies-the quiet, science-driven backbone of every generic drug approval. These aren’t just lab tests. They’re precise, controlled experiments that measure whether your body absorbs the generic drug at the same rate and to the same extent as the original. If they don’t match, the drug doesn’t get approved. And for millions of people who rely on generics to save money, this system is the reason they can trust their prescriptions.

What Bioavailability Actually Means

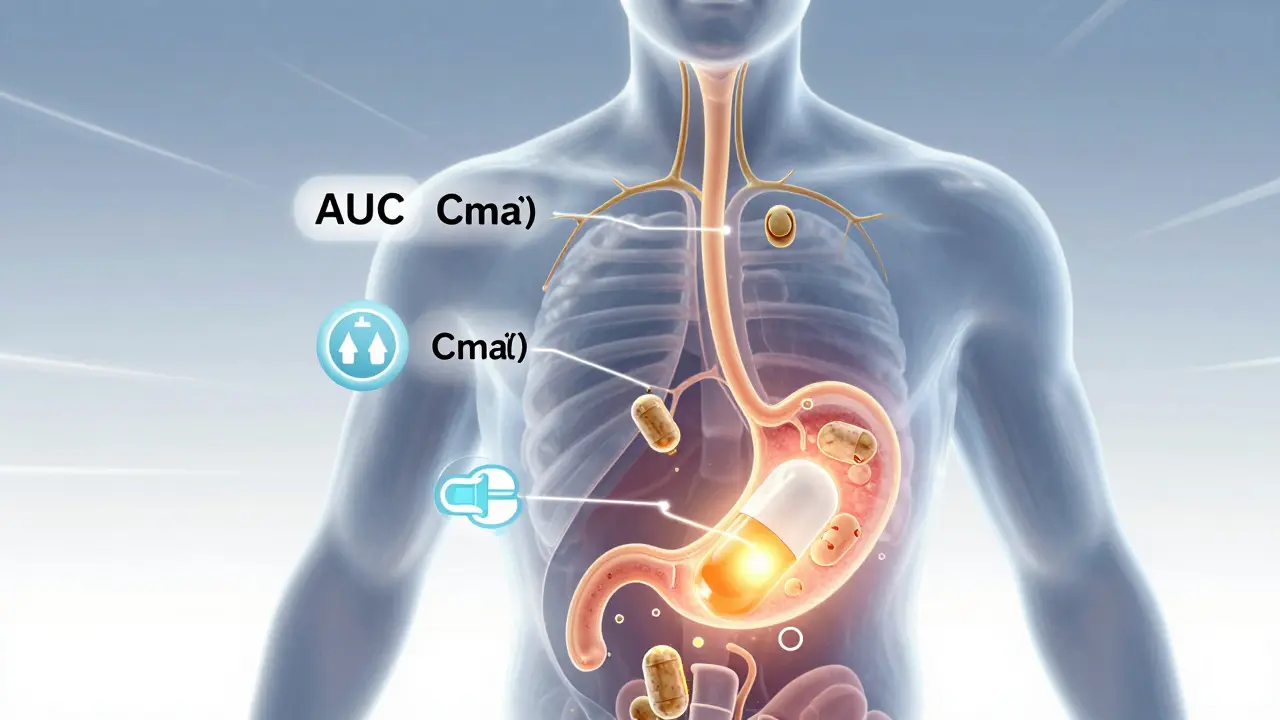

Bioavailability isn’t about whether a drug works. It’s about how much of it gets into your bloodstream-and how fast. Think of it like pouring water into a cup. If you dump it all at once, the cup fills quickly. If you drip it slowly, it takes longer. The total amount might be the same, but how your body responds changes. That’s why bioavailability looks at two key numbers: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration).

AUC tells you the total exposure over time. It’s the full picture: how much drug your body absorbs from start to finish. Cmax shows the peak level-how high the concentration goes in your blood. Together, they answer: Did the generic drug get into your system the same way as the brand? A third number, Tmax (Time to Maximum Concentration), tells you how quickly it peaks. A difference here might mean the generic kicks in faster or slower, which matters for drugs that need to act at specific times, like pain relievers or heart medications.

How the FDA Tests for Bioequivalence

The FDA doesn’t just compare one number. It demands a full pharmacokinetic profile. In a typical bioequivalence study, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers take both the brand-name drug and the generic, in random order, with a clean break-usually five half-lives-between doses. Blood samples are drawn every 15 to 60 minutes over 24 to 72 hours, depending on how long the drug stays in the body. These samples are analyzed using highly validated methods to measure exact concentrations.

The magic number? 80% to 125%. For a generic to pass, the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand for both AUC and Cmax must fall within that range. That means the generic’s absorption can’t be more than 25% higher or 20% lower than the original. It’s not a guess. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing that differences outside this range are unlikely to affect safety or effectiveness for most drugs.

But here’s the catch: some drugs are trickier. Take warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine. These have narrow therapeutic windows-tiny changes can cause big problems. For these, the FDA tightens the rules. The acceptable range shrinks to 90%-111%. A 10% difference in absorption might mean a stroke risk or a seizure. That’s why these drugs get extra scrutiny.

When the Rules Get More Complex

Not all pills are created equal. Extended-release tablets, inhalers, gels, and patches don’t behave like simple immediate-release drugs. A tablet that releases over 12 hours isn’t the same as one that drops its dose all at once. For these, the FDA requires multiple time-point comparisons. For example, a generic testosterone gel must show equivalence not just in overall exposure, but also at specific hours after application-because skin absorption varies.

And then there are highly variable drugs. Some people’s bodies absorb them wildly differently-due to metabolism, diet, or genetics. For these, the FDA allows something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). If the brand drug itself shows high variability in studies, the acceptable range can widen to 75%-133%. This happened with tacrolimus, a transplant drug. Without RSABE, no generic would have passed. With it, safe, effective versions reached patients.

What About Waivers? Can a Generic Skip Testing?

Yes-and it’s not a loophole. The FDA allows BCS waivers for certain drugs based on their physical properties. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) groups drugs by solubility and permeability. Class 1 drugs-highly soluble and highly absorbable-like atorvastatin or metformin-can qualify for a waiver if their formulation matches the brand exactly. No human study needed. Why? Because science shows their absorption is so predictable that differences in excipients (fillers) won’t change outcomes.

Class 3 drugs, like amoxicillin, are highly soluble but less permeable. They can also qualify if they dissolve quickly and have the same ingredients. But even here, the FDA requires proof of identical dissolution profiles in lab tests. It’s not a shortcut. It’s a smarter use of science.

Real-World Concerns: Do Generics Always Work the Same?

Some patients swear their generic doesn’t work like the brand. A cardiologist in Toronto told me about three patients who developed palpitations after switching from brand-name amlodipine to a generic. All improved when they switched back. But out of 3,000 patients? That’s less than 0.1%. The Epilepsy Foundation tracked 187 reports of increased seizures after switching generics-but only 12 cases were even possibly linked to bioequivalence issues. Most were due to missed doses or other factors.

The data supports this. Since 1984, over 15,000 generic drugs have been approved by the FDA. Ninety-seven percent of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics. And yet, there’s no documented case of a therapeutic failure caused solely by bioequivalence limits for standard oral drugs. The system works. It’s not perfect, but it’s rigorously tested.

What’s Changing in Bioequivalence Testing?

The field is evolving. The FDA is now using machine learning to predict bioequivalence from formulation data. In a 2023 pilot with MIT, AI models predicted AUC ratios with 87% accuracy across 150 drugs. That could cut down the number of human studies needed. For complex generics-like inhalers or injectables-new product-specific guidances are being issued to define exactly how equivalence should be measured.

Another shift? The move toward model-informed drug development. Instead of running 30-person studies, companies might use computer simulations based on existing data to predict absorption. It’s faster, cheaper, and still scientifically valid. The FDA is open to it-if the model is proven.

But one thing hasn’t changed: the gold standard is still the human study. Blood samples, controlled conditions, precise measurements. Why? Because biology is messy. No lab test or algorithm can fully replace how a real human body absorbs a drug.

Why This All Matters

Generics save the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion a year. Without bioavailability studies, we’d have no way to guarantee those savings don’t come at the cost of safety. The 80-125% rule isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on clinical evidence, statistical rigor, and decades of real-world use. It’s the reason you can trust that your $4 generic blood pressure pill works as well as the $150 brand.

For patients, the message is simple: if a generic is FDA-approved, it’s been proven to behave like the brand in your body. For doctors, it means you can prescribe with confidence. For manufacturers, it’s a high bar-but one that ensures fairness and safety across the board.

The science isn’t flashy. No headlines. No viral videos. Just carefully designed studies, blood samples, and statistical analysis. But it’s the quiet foundation of affordable medicine. And right now, it’s working better than ever.

What’s the difference between bioavailability and bioequivalence?

Bioavailability measures how much and how fast a drug enters your bloodstream after you take it. Bioequivalence compares two versions of the same drug-usually a generic and a brand-to see if they have the same bioavailability. A generic must show bioequivalence to be approved.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

A small number of patients report differences, especially with drugs like thyroid hormone or seizure medications. But investigations show most of these cases aren’t due to bioequivalence failures. They’re often caused by switching between different generic brands, missed doses, or other health factors. The FDA and independent studies confirm that approved generics perform the same as brand-name drugs for the vast majority of people.

Are all generics tested on humans?

Most are-but not all. Some simple, highly soluble drugs (BCS Class 1 or 3) can qualify for a waiver if their formulation matches the brand exactly. In those cases, lab tests showing identical dissolution rates are enough. For complex drugs, extended-release forms, or narrow therapeutic index drugs, human studies are required.

What happens if a generic fails bioequivalence testing?

It’s not approved. The company must go back, change the formulation, and resubmit. Many generics fail the first time. The process is strict for a reason: if a drug doesn’t meet the 80-125% range, it could be less effective or cause side effects. The FDA doesn’t compromise on this.

Can a generic be approved even if it’s not exactly the same as the brand?

Yes-but only if it behaves the same in your body. Generics can have different inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, coatings), and that’s normal. What matters is that the active ingredient is absorbed at the same rate and extent. The FDA doesn’t require identical ingredients-just identical performance.

Heather Josey

January 2, 2026 AT 06:28The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are one of the quietest triumphs of modern pharmacology. I work in clinical research, and I’ve seen how painstakingly these studies are designed-every blood draw timed, every volunteer monitored, every statistical margin justified. It’s not glamorous, but it’s what keeps people safe while keeping meds affordable. Seriously, next time you grab a $4 generic, give a little nod to the scientists who made sure it’s not just cheap-it’s reliable.

And yes, I’ve had patients panic about switching, but 99% of the time, it’s anxiety, not pharmacology. The data doesn’t lie.

sharad vyas

January 4, 2026 AT 04:39in india we have many generics. some good some bad. but the system here is not like usa. here medicine is sold like snacks. no one checks. no one cares. but i think what usa do is right. if body take same amount then it is same. simple. no need to make it hard.

but why some people feel different? maybe their mind think it is not brand so it must not work. mind is strong. body follows mind.

Dusty Weeks

January 4, 2026 AT 13:02bro the fda is just being extra. like why do we need 24 people to drink pills and get poked? 🤡 we got AI now. just simulate it. also why is the range 80-125? sounds like they picked it outta their butt. i switched from brand to generic for my anxiety med and i felt like a zombie for a week. coincidence? i think not. 🤨

Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 5, 2026 AT 04:34LOL I had a friend who swore her generic levothyroxine made her feel like a zombie. She switched back to Synthroid and felt ‘like herself again.’ So we all rolled our eyes… until she got her bloodwork done. Turns out her TSH was off by 3 points. The generic was fine-it was just that she’d been on the wrong dose for years and the brand had accidentally been masking it. Generics aren’t the problem. Inconsistent dosing and placebo mindset are. 🙃

Also-thank you for explaining RSABE. I didn’t know that existed. That’s wild how smart the FDA is about edge cases.

Layla Anna

January 6, 2026 AT 01:17i never thought about how much science goes into something so simple as a pill

but now that i think about it… why do some generics look different? different color? different shape? if they’re the same why not make them look identical? just saying

also i’ve heard people say their generic blood pressure med makes them dizzy… is that even possible if it’s bioequivalent?

maybe it’s the fillers? i dont know but i’m curious now

Donna Peplinskie

January 6, 2026 AT 06:39I just want to say-thank you for writing this. So many people dismiss generics as ‘inferior,’ but they don’t understand the science behind them. I’ve been on generic statins for 8 years. My cholesterol is stable. My bank account is happy. And my doctor says I’m in the green. It’s not magic-it’s math. And that math is solid.

Also, the part about BCS waivers? Mind blown. I had no idea some drugs could skip human trials because they’re so predictable. That’s brilliant. Not lazy. Brilliant.

Olukayode Oguntulu

January 7, 2026 AT 21:35ah yes, the FDA-guardian of the Western pharmaceutical oligarchy. How quaint that we still cling to this archaic model of blood draws and human guinea pigs when we could be using quantum pharmacokinetic modeling or AI-driven synthetic bioassays. The 80-125% paradigm is a relic of the 20th century, a crude heuristic born from the limitations of analog lab equipment and underfunded research. We are now in the age of predictive digital twins and in silico clinical trials. Why are we still forcing healthy volunteers to swallow capsules like it’s 1992? The system is not rigorous-it’s nostalgic. And frankly, it’s a barrier to innovation. The real scandal isn’t generics-it’s the institutional inertia protecting outdated paradigms.

jaspreet sandhu

January 8, 2026 AT 14:29you say the system works but i have seen too many cases where people get sick after switching to generic. i am not saying all generics are bad but the fact that you can change the fillers and still get approved means that the drug is not the same. the active ingredient might be the same but the body reacts to the whole thing not just one chemical. also why do some generics cost less than others if they are all the same? because they are not. the ones that cost more are better made. the cheap ones use bad fillers that make the pill dissolve too fast or too slow. the fda is not perfect. they are just trying to save money like everyone else.

Alex Warden

January 8, 2026 AT 23:14americans are too trusting. you let some foreign factory in china or india make your medicine and then you pat yourself on the back for being cheap? the fda approves it? big deal. they’re underfunded and overworked. they don’t even inspect half the plants. my cousin works at a pharma distributor-he says 30% of generics fail their own internal quality checks before they even ship. the fda doesn’t catch it. you think your $4 pill is safe? you’re lucky if it’s not laced with chalk and dust. we need american-made meds. period.

LIZETH DE PACHECO

January 9, 2026 AT 02:00Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read. I’m a nurse and I’ve had so many patients scared to switch to generics. I always say: ‘If the FDA says it’s the same, your body doesn’t know the difference.’ And honestly? Most of them feel better knowing the science behind it. Thanks for making it so easy to understand.

Also-love the part about AI predicting bioequivalence. That’s the future. Less human testing, more accurate results. Win-win.