When your heart muscle doesn’t work right, it doesn’t just feel like fatigue-it can be life-threatening. Cardiomyopathy isn’t one disease. It’s a group of conditions where the heart muscle changes shape, thickens, or stiffens, making it harder to pump blood. The three main types-dilated, hypertrophic, and restrictive-each have unique causes, symptoms, and treatments. Knowing the difference isn’t just medical jargon; it’s what separates effective care from dangerous missteps.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: The Enlarged, Weak Heart

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the most common type, making up about half of all cases. The heart’s main pumping chamber-the left ventricle-gets stretched and thinned. Instead of squeezing hard, it flaccidly expands like an overinflated balloon. This means less blood gets pushed out with each beat. Ejection fraction, a measure of how much blood the heart pumps out, often drops below 40%. Normal is 55-70%.

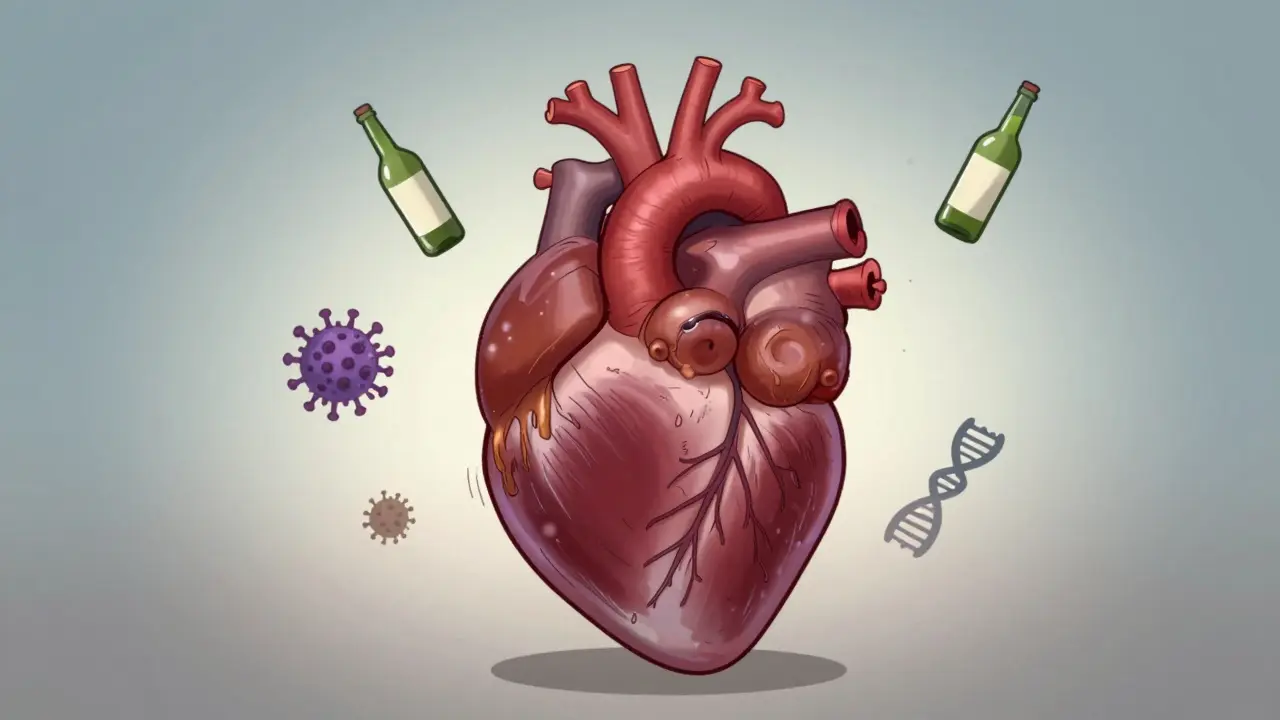

People with DCM often feel winded climbing stairs, swell in their legs and belly, and get dizzy from low blood pressure. Many don’t realize anything’s wrong until they collapse or develop heart failure. About one in 2,500 adults has it. In families, it’s often inherited-mutations in genes like TTN or LMNA cause about a third of cases. But it’s not always genetic. Heavy alcohol use over years (more than 80 grams daily), viral infections like coxsackievirus, chemotherapy drugs like doxorubicin, and autoimmune diseases like sarcoidosis can all trigger it.

Diagnosis starts with an echocardiogram. If the left ventricle is larger than 55 mm in men or 50 mm in women, and the wall is thin (under 10 mm), DCM is likely. Cardiac MRI adds detail, showing scarring or inflammation. Genetic testing is recommended if there’s a family history. Treatment isn’t about fixing the shape-it’s about supporting function. The standard combo-ARNI (like sacubitril/valsartan), beta-blockers, SGLT2 inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists-cuts death risk by 30% over three years. In severe cases, an ICD or even a heart transplant may be needed. About 70-80% of people survive five years with proper care.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The Thickened, Overworked Heart

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the opposite problem: the heart muscle grows too thick-often without warning. Walls of the left ventricle hit 15 mm or more, sometimes even 30 mm. This isn’t from high blood pressure or athletic training. It’s genetic. Mutations in sarcomere genes like MYH7 or MYBPC3 cause the muscle cells to grow abnormally, twisting into a chaotic pattern. The heart becomes stiff, struggles to fill with blood, and can block its own outflow tract.

One in 500 people has HCM, but many never know it. In athletes, it’s the top cause of sudden death under age 35. Symptoms include chest pain during exercise, fainting spells, and extreme shortness of breath. Some people feel fine until they collapse. About 70% have obstructive HCM, where the thickened septum blocks blood leaving the heart. That’s measured as a gradient over 30 mmHg during activity.

Diagnosis relies on echocardiography and cardiac MRI. If the wall is over 13 mm and there’s a family history, HCM is suspected. Genetic testing finds a mutation in 60% of cases. But here’s the catch: not everyone with the gene gets sick. That’s why family screening is critical. Treatment starts with beta-blockers-70% of patients see symptom relief. For those with obstruction, disopyramide helps. If meds fail, a septal myectomy (surgical removal of excess tissue) or alcohol septal ablation can open the outflow tract. About 85% of patients who get this procedure report immediate improvement. A new drug, mavacamten (Camzyos), approved in 2022, reduces obstruction by 80% in trials. The 5-year survival rate for non-obstructive HCM is 95%. For obstructive, it’s 70%.

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: The Stiff, Refusing Heart

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is the rarest-only 5% of cases-but often the most deadly. The heart muscle doesn’t get thick or stretchy. It gets stiff. Like a rubber band that lost its elasticity, it can’t relax enough to fill with blood. The ventricles stay small, the walls aren’t thick, but the heart can’t take in enough blood between beats. Ejection fraction stays normal or near normal-sometimes even above 50%. But the person still feels like they’re drowning.

People with RCM get swollen legs, belly fluid, and extreme fatigue. They’re often misdiagnosed because their heart looks fine on a basic echo. The real problem? The cause. Sixty percent of RCM cases come from amyloidosis-abnormal proteins (light chains) building up in the heart. Other causes: sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis (iron overload), and rare genetic storage diseases like Fabry disease.

Diagnosis is tricky. Echocardiography shows a restrictive filling pattern: blood rushes in fast, then stops abruptly (E/A ratio >2, deceleration time <150 ms). Cardiac MRI picks up abnormal tissue patterns-late gadolinium enhancement outside the coronary arteries. Biopsy is often needed to confirm amyloid. The big challenge? Telling RCM apart from constrictive pericarditis. One is the heart itself stiffening. The other is the sac around the heart hardening. They look alike on imaging, but one needs surgery, the other doesn’t.

Treatment targets the root cause. For amyloidosis, drugs like tafamidis (costing $225,000 a year in the U.S.) slow progression and improve walking distance by 25 meters. For hemochromatosis, regular blood removal (phlebotomy) helps. For sarcoidosis, steroids or immunosuppressants are used. But if the damage is advanced, transplant is often the only option. Survival is grim: 30-50% at five years, depending on the cause. Many patients wait months-or years-for the right diagnosis. One Reddit user wrote: “I went to seven doctors before someone said, ‘It’s not anxiety. It’s amyloid.’”

Why the Difference Matters

These aren’t just different shapes-they’re different diseases with different rules. Mistake HCM for DCM, and you give the wrong drugs. Mistake RCM for heart failure from high blood pressure, and you miss the real enemy. A 2023 audit found that 35% of community hospitals misclassify cardiomyopathy types. That’s not just a technical error. It’s a death sentence waiting to happen.

DCM? Focus on improving pump function and preventing arrhythmias. HCM? Focus on reducing obstruction and preventing sudden death. RCM? Focus on identifying the infiltrating disease before it’s too late. Genetic testing, advanced imaging, and specialized centers make all the difference. The global market for cardiomyopathy diagnostics is growing fast-$1.2 billion in 2023-with gene panels, cardiac MRI, and biomarkers like NT-proBNP becoming standard.

And it’s getting more precise. In 2024, CRISPR-based gene therapy for HCM entered early human trials. Polygenic risk scores may soon predict who’s likely to develop HCM before symptoms appear. The goal isn’t just to manage the disease-it’s to stop it before it starts.

What You Should Know

If you have a family history of sudden cardiac death before age 50, unexplained heart failure, or fainting during exercise-get screened. An EKG and echocardiogram are simple, noninvasive, and life-saving. Don’t wait for symptoms. Many people with HCM feel fine until it’s too late.

If you’re on chemotherapy, especially doxorubicin, ask about cardiac monitoring. If you drink heavily and feel tired, get your heart checked. If you have unexplained swelling and normal blood pressure, don’t assume it’s just aging. Ask about amyloidosis.

Cardiomyopathy isn’t rare. It affects 1 in 250 adults. But most people don’t know it exists. And that’s the real danger.

Can you live a normal life with cardiomyopathy?

Yes, many people do-with the right diagnosis and treatment. People with dilated cardiomyopathy on guideline therapy often return to work, travel, and exercise with restrictions. HCM patients can live long lives if they avoid intense competitive sports and take meds. RCM is harder; survival depends on the cause, but early treatment improves outcomes significantly. Lifestyle changes like low-salt diets, avoiding alcohol, and regular monitoring are key.

Is cardiomyopathy hereditary?

Yes, especially dilated and hypertrophic types. About 30-40% of DCM and 60% of HCM cases have a genetic cause. If a parent has it, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the gene. Genetic testing and family screening are now standard for these types. Restrictive cardiomyopathy is less often inherited, but some forms like Fabry disease are X-linked and run in families.

Can exercise help with cardiomyopathy?

It depends on the type. For dilated cardiomyopathy, moderate aerobic activity like walking or cycling is encouraged and improves heart function. For hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, intense exercise is dangerous-it can trigger sudden death. Most patients are advised to avoid competitive sports and heavy lifting. For restrictive cardiomyopathy, activity is limited by symptoms, but light walking is usually safe. Always consult a cardiologist before starting any program.

What’s the difference between cardiomyopathy and heart failure?

Cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle itself. Heart failure is a syndrome-what happens when the heart can’t pump well enough. Cardiomyopathy often leads to heart failure, but not all heart failure comes from cardiomyopathy. Blockages from coronary artery disease or leaky valves can also cause heart failure. That’s why doctors rule out those causes first before diagnosing cardiomyopathy.

Are there new treatments on the horizon?

Yes. For HCM, mavacamten (Camzyos) reduces obstruction and symptoms. For amyloidosis-related RCM, tafamidis and new drugs like diflunisal and patisiran are improving survival. Gene therapies using CRISPR are in early trials for HCM. For DCM, gene therapy trials (like AAV1/SERCA2a) aim to restore calcium handling in heart cells. These aren’t cures yet-but they’re turning once-fatal conditions into manageable ones.

What Comes Next

Early detection saves lives. If you have a family member who died suddenly under 50, or if you’ve been told your heart is “just a little enlarged” or “thickened,” push for a full evaluation. Don’t settle for “we’ll watch it.” Demand an echocardiogram, consider cardiac MRI, and ask about genetic testing. The tools exist. The knowledge exists. What’s missing is awareness.

Cardiomyopathy isn’t a death sentence. But it’s not something you can ignore. The heart doesn’t warn you. It just stops.

Natasha Plebani

January 29, 2026 AT 21:26The structural heterogeneity of cardiomyopathies isn't just a classification exercise-it's a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize heart failure as a syndrome rather than a single endpoint. DCM's TTN truncations, HCM's sarcomere disarray, RCM's amyloid fibril deposition-each represents a distinct molecular pathology with divergent downstream signaling cascades. The clinical utility of genetic stratification is no longer theoretical; it's altering therapeutic trajectories, particularly in presymptomatic families where early intervention with SGLT2 inhibitors or mavacamten can delay phenotypic expression by years.

What's underappreciated is how the same genetic variant can manifest differently across populations due to modifier genes or epigenetic regulation. That's why blanket recommendations for family screening must be contextualized with ancestry-specific penetrance data.

Kelly Weinhold

January 31, 2026 AT 12:49I just want to say how amazing it is that we're finally moving past the old 'one-size-fits-all' heart failure approach. I have a cousin who was misdiagnosed for years with 'just anxiety' until they found out she had HCM-now she's on mavacamten and hiking again. It gives me hope that with better awareness and testing, no one else has to suffer in silence like she did. Keep spreading this kind of info-it saves lives.

Kimberly Reker

February 1, 2026 AT 10:48Really well explained. I work in primary care and see so many patients dismissed as 'out of shape' when they're actually showing early signs of restrictive patterns. The key is recognizing that normal EF doesn't mean normal heart function. If someone's got unexplained fatigue, edema, and a normal echo, think RCM. Run the serum free light chains. Check ferritin. Don't stop at the basics.

Also, shoutout to the folks doing genetic counseling in rural areas-this stuff is life-changing when it reaches people who don't have easy access to specialists.

Rob Webber

February 3, 2026 AT 09:56This is all textbook nonsense. You people act like these are separate diseases when they're just different stages of the same underlying dysfunction. DCM isn't 'enlarged'-it's failing. HCM isn't 'thickened'-it's compensating. RCM isn't 'stiff'-it's fibrotic. Stop pretending taxonomy equals understanding. The real problem is we treat the anatomy, not the biology.

calanha nevin

February 3, 2026 AT 13:51Lisa McCluskey

February 5, 2026 AT 05:27owori patrick

February 6, 2026 AT 03:15This is beautiful. In Nigeria, we rarely have access to cardiac MRI or genetic testing, but even basic echo can detect these patterns if you know what to look for. We need more training for community health workers. This kind of clarity helps us advocate for better resources. Thank you for writing this.

Darren Gormley

February 7, 2026 AT 22:37LOL you all are so serious about this. 😂 I mean, sure, the science is cool, but let's be real-most people with DCM are just lazy and eat too much pizza. And HCM? Probably just people who lift too heavy without stretching. RCM? Must be from drinking too much coffee. Just sayin'. 🤷♂️

Amy Insalaco

February 9, 2026 AT 16:56The reductionist framing of these entities as discrete clinical phenotypes obscures the deeper truth: they are all manifestations of a dysregulated mechanotransduction pathway under chronic biomechanical stress. The current diagnostic hierarchy-echocardiography followed by MRI, then genetic testing-is not merely algorithmic; it is epistemologically flawed. We privilege structural imaging over molecular phenotyping, thereby perpetuating a Cartesian dichotomy between form and function that is fundamentally untenable in cardiac pathophysiology. The emergence of mavacamten as a targeted sarcomere modulator demands a paradigm shift from phenotypic classification to genotypic stratification as the new gold standard.

Katie and Nathan Milburn

February 10, 2026 AT 17:08It is important to recognize that the prevalence estimates cited are derived from predominantly Caucasian cohorts. Population-specific variations in gene expression and environmental modifiers may significantly alter the epidemiological profile in non-Western populations. Further global research is warranted to ensure equitable diagnostic and therapeutic access.

Marc Bains

February 10, 2026 AT 17:58As someone from a community where heart disease is often seen as 'God's will' or 'bad luck,' this breakdown matters. We need to bring this info to mosques, churches, barbershops-everywhere. My uncle thought his shortness of breath was just aging. Turns out he had DCM from years of heavy drinking. He's on meds now. We need more education like this, not just in hospitals but in neighborhoods.

kate jones

February 12, 2026 AT 12:22The 70–80% five-year survival in DCM is misleading without context. It assumes adherence to quadruple therapy-ARNI, beta-blocker, SGLT2i, MRA-which remains low in underserved populations due to cost, access, and health literacy barriers. Survival data must be disaggregated by socioeconomic status, not just clinical markers. Otherwise, we risk celebrating progress that only benefits the privileged.

Eliana Botelho

February 12, 2026 AT 18:12Okay but what if you're a 22-year-old athlete who passed every stress test and then just dropped dead during a pickup game? Like, how is that even possible? Everyone says 'genetic' but no one ever says what to DO about it. Should we all get genetic testing before we play sports? Who pays for it? This feels like a luxury problem for rich people with good insurance.

And why is no one talking about how HCM is basically the reason we have those 'no contact sports' warnings for kids? It's like we're scared to say it out loud: some people are just ticking time bombs and we don't have the tools to find them before it's too late.

Jodi Olson

February 13, 2026 AT 19:22Claire Wiltshire

February 13, 2026 AT 22:51Thank you for this comprehensive overview. The integration of genetic testing into routine clinical workflows remains underutilized, particularly in early-onset cases. Early identification of pathogenic variants enables proactive monitoring of asymptomatic relatives, significantly improving long-term outcomes. Multidisciplinary care teams-including genetic counselors, cardiologists, and psychologists-are essential to navigate the psychosocial implications of inherited cardiac conditions.