Every year, 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty because they can’t afford basic medicine. In many low-income countries, a single course of antibiotics or antiretroviral drugs can cost more than a week’s wages. Yet the solution already exists: generic medicines. These are exact copies of branded drugs, made after patents expire, and they can cost up to 80% less. So why are billions still going without?

What Generics Really Are - And Why They Matter

Generics aren’t cheap knockoffs. They contain the same active ingredients, work the same way, and meet the same safety standards as the original brand-name drugs. The difference? No marketing, no patents, no profit margins built on exclusivity. A generic version of HIV medication that once cost $10,000 a year now costs under $100 in many African countries. That’s not magic - it’s economics.The global generic drug market was worth $409 billion in 2022. But most of that money didn’t reach the people who need it most. In high-income countries like the U.S., generics make up 85% of all prescriptions by volume. In low-income countries? Only 5%. That gap isn’t about supply - it’s about systems.

Why Generics Haven’t Taken Off in Poorer Nations

You’d think if a drug works and costs pennies, everyone would use it. But reality is messier. In many low-income countries, the problem isn’t that generics don’t exist - it’s that they’re hard to find, hard to trust, and hard to afford even at low prices.First, supply chains are broken. A shipment of generic antimalarials might sit for months at a port because of customs delays or lack of refrigeration. In rural clinics, shelves are empty not because drugs are unavailable globally, but because they never made it past the last distributor.

Second, there’s deep distrust. Many patients and even doctors still believe branded drugs are better. This isn’t just ignorance - it’s a legacy of bad experiences. In some regions, fake or substandard drugs have flooded markets, making people wary of anything that doesn’t come in a familiar box. Even when generics are safe and WHO-certified, the stigma sticks.

Third, out-of-pocket payments dominate. Nearly 90% of people in low-income countries pay for medicine themselves. So even if a generic costs $5 instead of $50, it’s still too much for someone living on $2 a day. No insurance. No subsidies. No safety net.

The Companies That Are Trying - And Where They’re Falling Short

Five big generic manufacturers - Cipla, Hikma, Sun Pharma, Teva, and Viatris - produce about 90% of the off-patent drugs needed in low-income countries. They’ve made huge strides. Cipla, for example, helped slash the price of HIV treatment in Africa by over 99% in the early 2000s.But a 2024 report from the Access to Medicine Foundation found a troubling pattern: these companies have access strategies for only 41 out of 102 essential drugs. And even then, few of those strategies actually target the poorest patients. Most focus on governments or NGOs buying in bulk - not on making sure the person walking into a small clinic in Malawi or Bangladesh can walk out with medicine in hand.

Big pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Novartis have their own programs, offering discounts or free drugs in poor countries. But their reporting is vague. How many people actually get the medicine? Where? For how long? No one knows. Transparency is missing.

Regulatory Walls and Trade Barriers

Even when generics are available and affordable, governments often make it harder to get them. Many low-income countries still charge high import tariffs on medicines. Some require local testing for every batch - a costly, slow process that delays access. Others have approval systems so slow that it takes years to register a generic drug that’s already been used safely elsewhere.The Geneva Network recommends simple fixes: remove tariffs, cut red tape, and let countries import generics from trusted sources without extra barriers. But political will is weak. In some places, local manufacturers lobby against imports because they fear competition - even if their own products are more expensive or less reliable.

And then there’s the issue of patents. While the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement lets poor countries produce or import generics during public health emergencies, many still don’t use those flexibilities. Why? Fear of trade pressure. Fear of lawsuits. Fear of being labeled as “non-compliant.”

Real-World Wins - And What They Teach Us

There are bright spots. In Rwanda, the government partnered with NGOs and generic producers to build a national supply chain for HIV and TB drugs. Today, over 95% of people needing treatment get it - and most of those drugs are generic. In Thailand, the government started producing its own generic antiretrovirals in the early 2000s and now exports them to other countries.These successes share common traits: strong leadership, transparent procurement, and a focus on the last mile. They didn’t wait for big pharma to fix things. They built their own systems.

Another example: Gilead’s clinical trials for a new long-acting HIV prevention drug in Uganda. Instead of testing only in wealthy countries, they included African participants - and made sure the drug would be affordable if approved. That’s not charity. It’s smart science.

The Real Barrier Isn’t Cost - It’s Investment

The WHO says every country should have at least 80% of essential medicines available at public health facilities. Globally, we’re at 50%. In some African countries, it’s below 30%.The Abuja Declaration in 2001 asked African nations to spend at least 15% of their budgets on health. As of 2022, only 23 of 54 countries met that target. That’s the root problem. No amount of cheap generics will fix a health system that’s underfunded, understaffed, and under-resourced.

Generics are the tool. But without strong public health infrastructure - trained workers, reliable storage, transport networks, data systems - the tool sits unused.

What Needs to Change - And Who Can Make It Happen

Change isn’t impossible. It’s just not happening fast enough. Here’s what’s needed:- Government action: Cut import taxes on medicines. Fast-track approval for WHO-prequalified generics. Invest in public health supply chains.

- Pharma accountability: Companies must report exactly how many patients get their drugs, where, and how much they pay. No more vague “access programs.”

- International support: Donors should fund local manufacturing in Africa and South Asia, not just import aid. Building local capacity means long-term sustainability.

- Public trust: Community health workers need training and tools to explain that generics are safe. Campaigns that use local languages and trusted voices can break down myths.

Big data is being adopted by 76% of health organizations in emerging markets - a sign that people know the system is broken and need better information. But data alone won’t fix it. Action will.

The Bottom Line

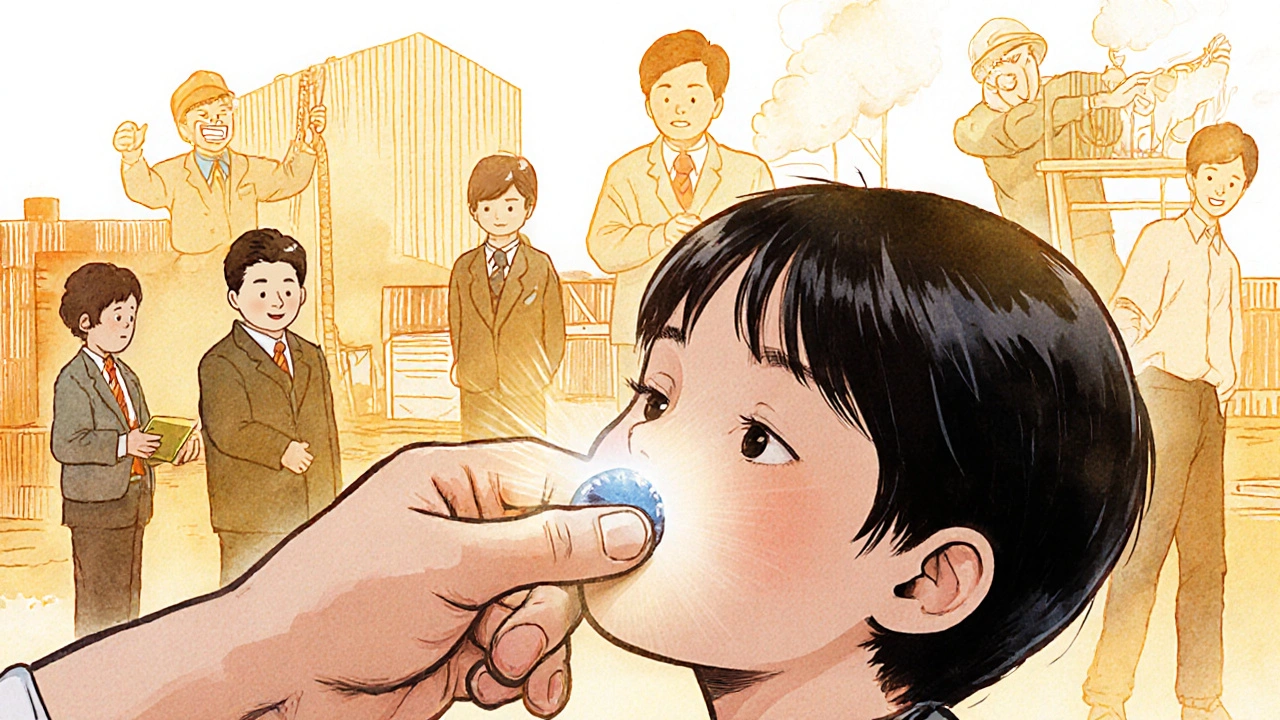

Generics have already saved millions of lives - from HIV in Africa to TB in India. They can do more. But they won’t unless we stop treating access as a technical problem and start treating it as a moral one.It’s not about whether a drug is cheap. It’s about whether a child in rural Mozambique can get it. Whether a mother in Pakistan can afford her diabetes medicine. Whether a farmer in Nepal can survive without selling his land to pay for his heart pills.

Generics aren’t the silver bullet. But they’re the only bullet we’ve got that actually works. The question isn’t whether we can afford to give them to everyone. It’s whether we can afford not to.

Laurie Sala

November 23, 2025 AT 16:21Why do we keep pretending this is just about money?? It’s not. It’s about power. It’s about who gets to live and who gets to suffer while some CEO buys another yacht. I’ve seen this in my own family-my cousin in Nigeria couldn’t get her HIV meds because the local pharmacy ‘ran out’-but the warehouse next door? Full. Full of generics. Just not for her. It’s cruel. It’s criminal. And we’re all just scrolling past it like it’s a TikTok trend!!!

Brandy Walley

November 24, 2025 AT 15:20shreyas yashas

November 25, 2025 AT 03:39Been working in rural clinics in Odisha for 12 years. I’ve seen the same story over and over. A box of generic ARVs arrives. Great. But the fridge is broken. The power’s out. The nurse hasn’t been paid in three months. So the meds sit. People don’t trust them because last year, someone died from a fake pill they thought was real. It’s not about the drug. It’s about the whole damn system falling apart. We need people on the ground-not just policies on paper.

Suresh Ramaiyan

November 26, 2025 AT 19:40There’s a quiet dignity in how communities adapt. In my village, elders started teaching younger ones to recognize WHO-certified logos. We made posters in Tamil. We held village meetings with the local pharmacist. Slowly, trust grew-not because someone from Geneva told us to, but because we saw our neighbor survive. Generics aren’t magic. But human connection? That’s the real medicine.

Katy Bell

November 28, 2025 AT 17:22I just cried reading this. Not because it’s sad-but because it’s so obvious. We have the tools. We have the science. We have the money. But we don’t have the will. And that’s the hardest thing to fix. How do you make someone care when they’ve never had to choose between rent and insulin?

Ragini Sharma

November 30, 2025 AT 07:04Linda Rosie

December 1, 2025 AT 03:47Vivian C Martinez

December 2, 2025 AT 13:58This is one of the most hopeful pieces I’ve read in months. Real change isn’t about grand gestures-it’s about consistent, quiet work. The clinics in Rwanda didn’t wait for permission. They just started. And now, kids are growing up with HIV under control. That’s the blueprint. We just need to copy it. Everywhere.

JD Mette

December 4, 2025 AT 00:33I’ve worked in supply chain logistics for 18 years. The bottleneck isn’t manufacturing. It’s paperwork. Every border crossing requires 17 forms. Each form takes 3 weeks to process. And if one signature is smudged? The whole shipment gets held. No one’s evil. No one’s lazy. It’s just… broken. We need one digital system. One. Not 17.

Olanrewaju Jeph

December 5, 2025 AT 12:24In Lagos, we had a pharmacy that sold fake malaria drugs. People died. Now, community leaders carry QR codes on their phones. Scan the box. See the batch number. See if it’s real. No government needed. Just neighbors helping neighbors. The tech exists. We just need to trust each other enough to use it.

Dalton Adams

December 6, 2025 AT 23:20Let’s be real-this isn’t a health crisis. It’s a capitalism failure. Big Pharma spent $20B on marketing last year. But only $200M on global access? That’s not a mistake. That’s a business model. And the WHO? They’re too scared to call it out. They take funding from the same companies they’re supposed to regulate. Wake up. This is corruption dressed as philanthropy. 🤡

Kane Ren

December 7, 2025 AT 10:30It’s not hopeless. Look at India-home to 1.4B people. They produce 60% of the world’s generics. They don’t wait for permission. They just make it happen. If they can do it, so can everyone else. We just need to stop seeing poor countries as victims and start seeing them as innovators.

Charmaine Barcelon

December 7, 2025 AT 14:28