When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way - not because the pill is different, but because of your genes? This isn’t rare. It’s happening to thousands of people every day, often without anyone realizing why.

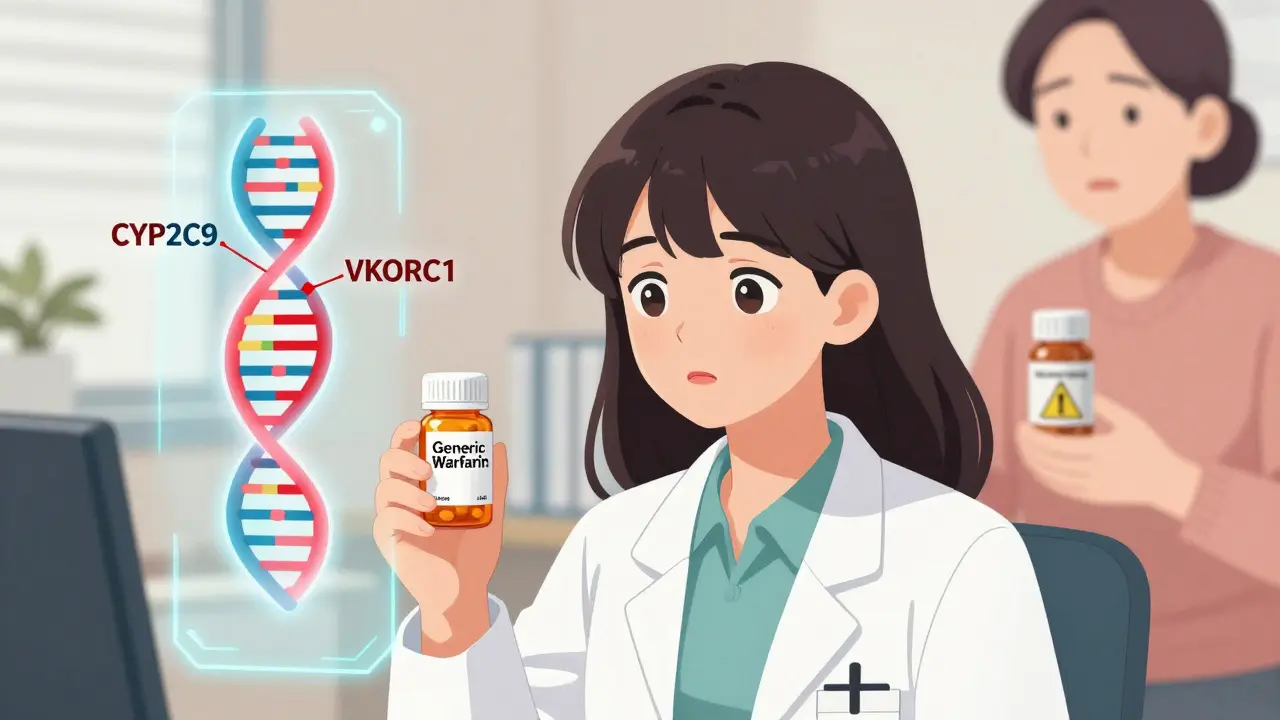

Take warfarin, a blood thinner commonly prescribed after a stroke or heart surgery. The generic version works just as well as the brand name - if your body can process it properly. But if you have a variant in the CYP2C9 or VKORC1 gene, your body might break down the drug too slowly. That means even a standard dose can build up to dangerous levels, increasing your risk of internal bleeding. And if you’re African American, you’re statistically more likely to carry variants that require a higher dose than what’s typically prescribed. Without knowing your genetics, you’re guessing.

This isn’t about brand names or cost. It’s about biology. And your family history holds clues.

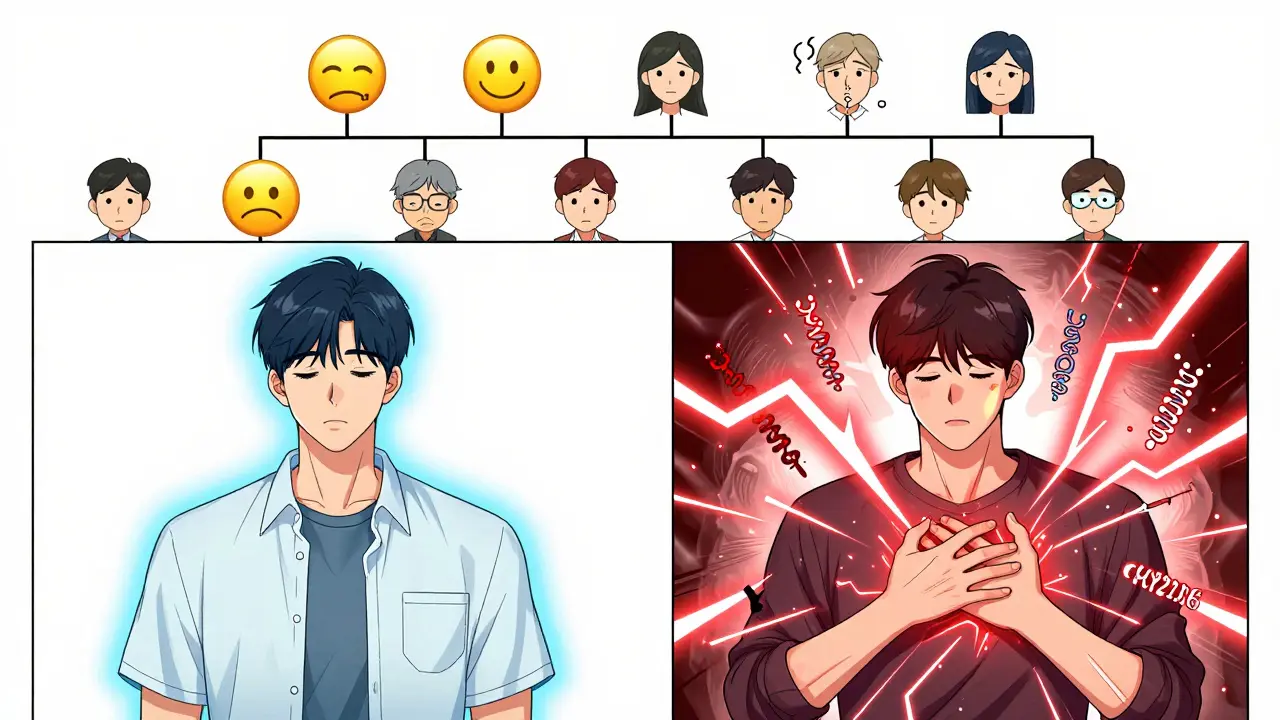

Your Family’s Drug Reactions Are a Genetic Map

Think about your parents or grandparents. Did your mom have a terrible reaction to a common antibiotic? Did your dad get severe nausea from a painkiller that worked fine for everyone else? These aren’t just bad luck. They’re signals - genetic red flags passed down through generations.

Studies show that between 20% and 95% of how you respond to a drug comes from your DNA. That’s not a small range - it means for some medications, your genes are the biggest factor in whether they work, cause side effects, or do nothing at all.

One of the most studied genes is CYP2D6. It handles about 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants like sertraline, beta-blockers like metoprolol, and even some opioids. If you’re a “poor metabolizer” for CYP2D6, your body can’t break down these drugs fast enough. You might get dizzy, nauseous, or even have serotonin syndrome - a life-threatening reaction. If you’re an “ultra-rapid metabolizer,” the drug gets cleared too quickly. It won’t work. Your doctor might increase the dose, thinking you’re not taking it right, when really, your genes are the issue.

And if your mother was a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, there’s a 50% chance you inherited that trait. That’s why asking about family reactions isn’t just small talk - it’s critical medical history.

Why Generics Can Feel Different - Even When They’re Not

Generic drugs are required by law to have the same active ingredient as the brand name. That’s true. But here’s the catch: generics can have different inactive ingredients - fillers, dyes, coatings. For most people, that doesn’t matter. But for someone with a rare genetic sensitivity, even a tiny change in formulation can trigger a reaction.

One patient in Toronto switched from brand-name Effexor to its generic venlafaxine and suddenly couldn’t sleep, felt jittery, and had heart palpitations. Her doctor assumed it was anxiety. But her genetic test showed she was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. The generic had a different coating that slowed absorption slightly - enough to push her into toxicity because her body couldn’t clear the drug at all. When she switched back to the brand, her symptoms disappeared. The active ingredient was the same. But the delivery wasn’t.

This doesn’t mean generics are unsafe. It means your body’s unique biology matters more than you think. And if you’ve had bad reactions to medications before - especially ones that worked fine for others in your family - your genes might be the reason.

The Genes That Matter Most

Not all genes affect every drug. But a few key ones are linked to common prescriptions:

- CYP2D6: Affects antidepressants, beta-blockers, opioids. Over 80 known variants. Poor metabolizers make up 5-10% of Caucasians, up to 20% in some Asian populations.

- CYP2C19: Impacts proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole), clopidogrel (a blood thinner), and some antidepressants. About 15-20% of Asians are poor metabolizers. In Caucasians, it’s 2-5%.

- CYP2C9 and VKORC1: Critical for warfarin dosing. Variants here can mean the difference between a safe dose and a life-threatening one.

- TPMT: For drugs like azathioprine and 6-MP, used in autoimmune diseases and cancer. People with low TPMT activity can develop life-threatening drops in white blood cells if given standard doses.

- DPYD: For chemotherapy drugs like 5-fluorouracil. A single variant can cause severe toxicity - even death - if not caught before treatment.

These aren’t obscure genes. They’re in your DNA right now. And if you’re taking any of these drugs - especially long-term - you’re playing Russian roulette without knowing the odds.

Population Differences Matter - Even for Generics

Genetic variants aren’t evenly spread. A variant that’s rare in one group can be common in another. That’s why one-size-fits-all dosing fails.

For example, the CYP2C19 poor metabolizer variant is found in 15-20% of East Asians but only 2-5% of Europeans. That means a standard dose of omeprazole might work perfectly for a Canadian of European descent but leave an Asian-Canadian with persistent acid reflux - not because the generic is weak, but because their body can’t activate it.

Same with warfarin. African Americans often need higher doses than Europeans because of genetic differences in VKORC1 and CYP2C9. But if your doctor doesn’t know your ancestry or genetic profile, they might start you on a dose meant for someone else. That’s not negligence - it’s a system built on averages, not individual biology.

And here’s the problem: most generic drug labels don’t mention genetics. They assume everyone responds the same. That’s outdated. The FDA now lists over 300 drugs with pharmacogenetic info on their labels - but that info rarely reaches the front lines.

Testing Is Available - But It’s Not Routine

Genetic tests for drug response aren’t science fiction. They’re real, affordable, and increasingly accurate.

Companies like Color Genomics and OneOme offer multi-gene panels for under $300. These tests look at CYP2D6, CYP2C19, TPMT, DPYD, and more. The results come back as a simple report: “You’re a poor metabolizer for CYP2D6. Avoid these drugs. Use alternatives.”

One patient in Hamilton, Ontario, had chronic migraines and tried six different triptans - all with bad side effects. Her test showed she was a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. The drugs were cleared before they could work. Her doctor switched her to a non-metabolized alternative - and within weeks, her headaches were gone.

But here’s the catch: 79% of doctors say they don’t have time to interpret the results. And 68% of clinicians feel confident reading CYP2D6 results - but only 32% feel comfortable with HLA-B*15:02, a gene linked to severe skin reactions from carbamazepine. That’s a gap.

Some hospitals - like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt - have built systems that automatically flag high-risk gene-drug combinations in electronic records. If you’re on clopidogrel and have a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer result, the system warns the prescriber. That’s the future. But it’s not the norm yet.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need a PhD to protect yourself. Here’s what actually works:

- Write down your family’s drug reactions. Not just “my mom had side effects.” Be specific: Which drug? What happened? Did it happen with generics too?

- Ask your doctor: “Could my genes affect how I respond to this?” Especially if you’ve had bad reactions before, or if the drug is on the list above.

- Request a pharmacogenetic test if you’re on long-term meds. Especially for antidepressants, blood thinners, painkillers, or chemotherapy.

- Keep your results with your medical records. Share them with every new doctor. It’s your health history - not just your family’s.

- Don’t assume generics are identical. If a generic causes new side effects, tell your pharmacist. Sometimes switching to a different generic (same active ingredient, different filler) helps.

There’s no magic pill. But knowing your genes gives you power. It stops the trial-and-error. It cuts down on hospital visits. It saves time, money, and pain.

Is This Worth the Cost?

A single pharmacogenetic test costs about $250. That’s less than one ER visit for a bad reaction. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study found that in 10,000 patients tested, 42% had a high-risk gene-drug interaction. Of those, 67% had their meds changed - and adverse events dropped by 34%.

For someone on warfarin, a genetic test can mean fewer blood draws, fewer hospitalizations, and less fear. For someone on chemotherapy, it could mean survival.

It’s not about being rich. It’s about being informed. And with Medicare covering some tests now and more insurers following, it’s becoming more accessible.

The Bottom Line

Switching to a generic drug should be safe. But if your body’s built differently - because of your genes, because of your family - it might not be. Ignoring genetics isn’t saving money. It’s gambling with your health.

The science is here. The tests are available. The data is clear. What’s missing is the conversation.

Ask your doctor. Talk to your family. Get tested if you’ve ever had a drug that didn’t work - or made you sick. Your genes are speaking. It’s time to listen.

Jaspreet Kaur Chana

January 14, 2026 AT 14:48Man, this hits home hard. My dad in Punjab had to be hospitalized after a generic clopidogrel turned his blood into syrup - turns out he’s a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer, and no one ever asked about his family’s history with aspirin reactions. My aunt had the same thing with omeprazole - thought she was just ‘sensitive,’ but it was genetics. We’re not talking rare here - in South Asia, this stuff is everywhere. Why are we still guessing when a $250 test could’ve saved him months of pain? I’ve been pushing my whole family to get tested. If you’re on meds long-term and your body says ‘no,’ don’t ignore it - your genes aren’t being dramatic, they’re screaming.

Haley Graves

January 16, 2026 AT 09:15This is exactly why personalized medicine isn’t a luxury - it’s a necessity. I work in a clinic in rural Ohio, and we see this every week. Patients on antidepressants who ‘don’t respond’ - turns out they’re CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers. Doctors blame noncompliance. It’s not compliance, it’s biology. We started offering in-house pharmacogenetic screening last year. Adverse events dropped 40%. The system is broken because it treats bodies like widgets. Stop assuming. Start testing.

Diane Hendriks

January 17, 2026 AT 14:34Let’s be clear: the FDA’s pharmacogenetic labeling is a joke. Over 300 drugs have genetic warnings on their labels - yet not one generic manufacturer is required to include them in packaging or patient inserts. This isn’t negligence - it’s corporate malfeasance. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex profits from trial-and-error prescribing. Why? Because if you keep patients on the same drug for years while they suffer side effects, you get repeat prescriptions. If you test them once and switch them to a safe alternative, you lose revenue. The system isn’t broken - it’s designed this way. Genetic testing is the only thing standing between you and a fatal reaction. And they want you to believe it’s too expensive. It’s not. It’s inconvenient for them.

Sohan Jindal

January 18, 2026 AT 20:04They don't want you to know this. Big Pharma and the government are hiding this. Why? Because if you knew your genes could make a drug kill you, you'd demand tests. And then they couldn't sell you the same cheap generic for 50 states. They're letting people die so they can save a dime. And now they want you to pay for the test? That's the trap. The real solution? Ban generics. Go back to brand names. They're safer. Always have been. This is all a scam to make you pay more for nothing. I saw a guy on YouTube say the same thing - his cousin died from a generic. They don't want you to talk about it.

Annie Choi

January 19, 2026 AT 18:15Just had a patient come in last week - CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer on sertraline. Six months of ‘anxiety flare-ups’ - turns out the drug was gone in 90 minutes. Switched to mirtazapine, no CYP2D6 metabolism, boom - mood stabilized in 10 days. We’re doing pharmacogenetic panels on all new psych patients now. It’s not rocket science. It’s basic pharmacokinetics. Why isn’t this standard? Because EMRs don’t auto-flag it. Because docs are overworked. Because insurance won’t cover it unless you’re already in the ER. We need policy change. Not just individual awareness. This is systemic. And it’s killing people quietly.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 20, 2026 AT 23:15Ha! I knew it. My uncle took warfarin after bypass surgery - ended up in ICU with internal bleeding. Doctor said, ‘You must’ve missed a dose.’ My aunt? Same thing. Then we found out - both have the VKORC1 variant. Classic. And now? I refuse to take anything without checking my ancestry first. If your grandparents died young on meds? You’re not unlucky - you’re genetically flagged. Stop being passive. Ask your doctor: ‘What’s my CYP2D6 status?’ If they stare blankly? Find a new doctor. This isn’t optional. It’s survival.

Jan Hess

January 21, 2026 AT 14:52I had a bad reaction to a generic ibuprofen - stomach cramps, dizziness. Thought it was just bad luck. Then I got tested after reading this - turns out I’m a CYP2C9 poor metabolizer. Switched back to the brand, no issues. The inactive ingredients weren’t the problem - it was my genes. I’m telling everyone now. If you’ve ever had a weird reaction to a common med, get tested. It’s not expensive. It’s not complicated. It’s just not common yet. But it should be. This is the future of medicine. We’re just early.

Iona Jane

January 23, 2026 AT 01:51They’re lying. All of them. The FDA, the drug companies, your doctor - they know. They know your genes can make a pill kill you. But they won’t tell you because if you knew, you’d stop buying. That’s why they bury the science. That’s why your insurance won’t cover the test. That’s why your pharmacist says ‘it’s the same.’ It’s not. It’s a death lottery and you’re the ticket. Don’t trust the system. Get tested. Or don’t. But don’t say I didn’t warn you when you’re in the ER with your organs shutting down.