When a drug is designed to release slowly over time - like a painkiller that lasts 12 hours instead of 4 - it’s called a modified-release formulation. These aren’t just fancy pills. They’re engineered to keep drug levels steady in your blood, reduce side effects, and make it easier to take your medicine once a day instead of four. But here’s the catch: just because two pills look the same doesn’t mean they work the same. For generic versions of these drugs, proving they’re equivalent to the brand-name version isn’t as simple as comparing one blood test to another. There are special rules - and they’re strict.

Why Modified-Release Is Different

Immediate-release pills dump their entire dose into your system within an hour. Modified-release (MR) drugs, like extended-release (ER) or delayed-release tablets, control how and when the drug gets released. This sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex dance of chemistry, physics, and biology. A single ER tablet might have multiple layers, beads, or coatings that dissolve at different times. Some release right away; others wait hours. That’s why a generic version that looks identical might still fail in your body.Take Ambien CR, for example. It has two parts: one layer releases zolpidem fast to help you fall asleep, and another kicks in later to keep you asleep. If the generic version releases too much too soon, you might wake up groggy. Too little too late, and you won’t stay asleep. The FDA requires testing both the early and late phases - called partial AUC (pAUC) - to make sure the generic matches the brand exactly in both. That’s not something you’d need for a regular aspirin.

The Bioequivalence Rules That Matter

For regular pills, bioequivalence (BE) is usually judged by two numbers: how much drug gets into your blood (AUC) and how high the peak level goes (Cmax). Both need to fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s it.For MR drugs, it’s not that simple. The FDA’s 2022 guidance says you need more. Here’s what’s required:

- Single-dose studies are preferred over multiple-dose. Why? Because with repeated dosing, the drug builds up in your body, and it’s harder to tell if differences come from the formulation or just accumulation.

- Partial AUC is mandatory for multiphasic products. For drugs like Concerta (methylphenidate ER), you must measure AUC from 0-2 hours (the fast release) and 2-∞ hours (the slow release). If the generic doesn’t match both, it’s rejected.

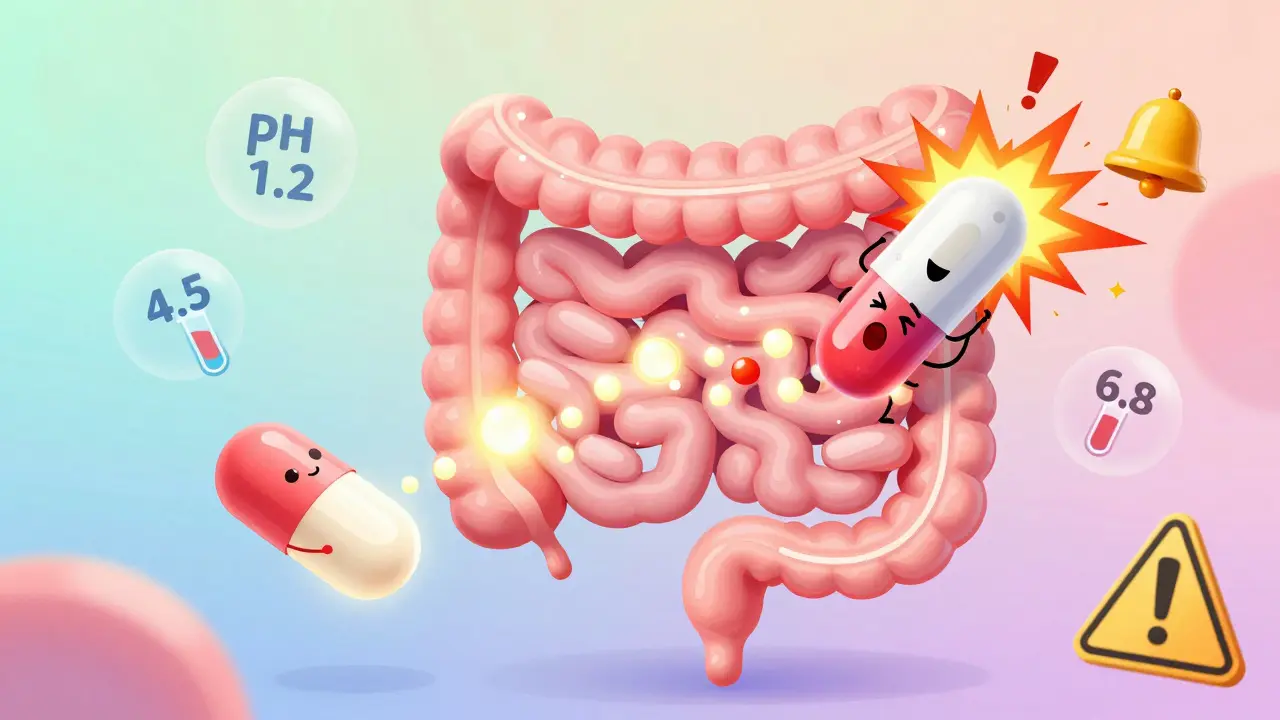

- Dissolution testing must be done at three pH levels: 1.2 (stomach), 4.5 (upper intestine), and 6.8 (lower intestine). This mimics how the pill behaves as it moves through your body. If the dissolution profile doesn’t match the brand at all three levels, the product fails - even if blood levels look fine.

- Alcohol testing is required for any ER product with 250 mg or more of active ingredient. Why? Alcohol can cause “dose dumping” - where the entire drug releases at once. Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER painkillers were pulled from the market because of this risk.

- RSABE is used for highly variable drugs (like warfarin or some antiepileptics). If the brand’s variability is above 30%, the acceptance range can widen - but only if the generic matches the brand’s variability too. This adds months to development and costs extra.

Regulatory Differences: FDA vs. EMA

The FDA and EMA (Europe’s drug agency) don’t always agree. The FDA says: test once, fast, and focus on release patterns. The EMA sometimes says: test multiple times until steady state is reached - especially if the drug builds up in your system.For example, if a drug accumulates more than 1.5 times with repeated dosing, the EMA may require a steady-state study. The FDA rarely does. Experts are split. Some, like Dr. Donald Mager, argue steady-state studies better predict real-world performance. Others, like former FDA director Vinod Shah, say single-dose studies are more sensitive to formulation differences.

And then there’s the biowaiver issue. The WHO says MR bioequivalence rules should be the same as for regular pills. The FDA and EMA say no - they’re fundamentally different. The FDA requires three pH dissolution points for ER tablets. For beaded capsules? Just one. The EMA uses similarity factors (f2) - if your dissolution curve matches the brand’s with an f2 score above 50, you might skip human studies altogether. But only if your formulation is simple enough.

Why So Many Generic MR Drugs Get Rejected

It’s not that companies are cutting corners. It’s that the science is hard. Between 2018 and 2021, 22% of MR generic applications were initially rejected by the FDA - mostly because they didn’t get the pAUC right. One infamous case was a generic version of Concerta. The company tested blood levels but didn’t measure the early release phase properly. The FDA said: “You didn’t prove the first part works.” They rejected it.Another common failure: dissolution testing. A Teva scientist reported on a pharmaceutical forum that 35-40% of early ER oxycodone formulations failed dissolution at pH 6.8. That’s the lower intestine - where the drug is supposed to keep releasing. If your tablet dissolves too fast there, it’s not extended-release anymore. It’s just a quick-release pill in disguise.

Even small changes matter. A formulation scientist at Sandoz succeeded with an ER tacrolimus generic by proving dissolution similarity at pH 6.8 alone (f2=68). They skipped the human study, saved $1.5 million, and got approval 10 months faster. But that only worked because their product had a simple, predictable release profile.

Cost and Complexity

Developing a generic MR drug costs $5-7 million more than a regular one. Why? Because you need:- Specialized dissolution equipment (USP Apparatus 3 or 4, not the standard 2)

- Advanced pharmacokinetic modeling software (like WinNonlin or NONMEM)

- Statistical experts who understand RSABE

- Multiple clinical sites with experience in MR BE studies

A single-dose MR bioequivalence study runs $1.2-1.8 million. An IR study? $0.8-1.2 million. That’s a big gap. And it’s why only big pharma and large CROs - like PRA Health Sciences, Covance, and ICON - dominate this space. Small biotechs rarely attempt it.

What Happens When Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

Even if a generic passes all the tests, it might still cause problems. A 2016 study in Neurology found that 18% of generic extended-release antiepileptic drugs had higher seizure breakthrough rates than the brand - even though they met all FDA bioequivalence standards. Why? Because BE tests measure total exposure and peak levels. They don’t measure subtle timing differences that matter for brain activity.This isn’t about safety - it’s about efficacy. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, like warfarin or lithium, even a small delay in release can mean the difference between a seizure and a stroke. That’s why the FDA tightened the acceptance range for NTI drugs to 90-111% instead of 80-125%.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working on a new 2024 guidance for complex MR products - things like gastroretentive systems (pills that float in your stomach) and multiparticulate beads. These are harder to test because they behave differently in every person.Meanwhile, companies are turning to computer models. PBPK (physiologically based pharmacokinetic) modeling lets them simulate how a drug behaves in the body without doing human trials. Sixty-eight percent of big pharma now use it for MR development. The FDA has accepted 12 biowaivers based on IVIVC (in vitro-in vivo correlation) models since 2019.

But the bottom line hasn’t changed: if you’re making a generic modified-release drug, you can’t cut corners. The rules are complex, the stakes are high, and the margin for error is tiny. One wrong dissolution curve. One missed pAUC. One alcohol test failure. And your $5 million investment goes nowhere.

How to Get Started

If you’re entering this field - whether as a pharmacist, regulator, or developer - here’s where to begin:- Read the FDA’s 2022 Bioequivalence Guidance (117 pages, but the key sections are 7-9 and 12).

- Study product-specific guidances (PSGs) for your drug - there are over 150 for MR products.

- Learn how to run dissolution testing at multiple pH levels and interpret f2 values.

- Understand partial AUC calculations and when they’re required.

- Practice RSABE statistical analysis - it’s not optional for highly variable drugs.

- Work with a lab experienced in ER BE studies. Don’t try to build this expertise from scratch.

There’s no shortcut. But there’s a path - if you’re willing to learn the details.

Why can't we just use the same bioequivalence rules for modified-release drugs as for immediate-release ones?

Because modified-release drugs are designed to release the drug slowly over time, not all at once. A standard bioequivalence test only checks total exposure (AUC) and peak level (Cmax). But for an extended-release pill, the timing of release matters just as much. If the generic releases too fast at first, you get side effects. Too slow, and it doesn’t work. That’s why regulators require partial AUC, dissolution profiles at multiple pH levels, and sometimes alcohol testing - things you don’t need for a regular aspirin.

What is pAUC and why is it important for drugs like Ambien CR?

pAUC stands for partial area under the curve. It measures how much drug gets into your blood during a specific time window. For Ambien CR, which has two release phases - fast for falling asleep, slow for staying asleep - regulators need to make sure both parts match the brand. So they test pAUC from 0 to 1.5 hours (the fast release) and from 1.5 hours to infinity (the slow release). If either part is off, even if the total AUC is fine, the generic fails.

Why do some generic MR drugs fail dissolution testing at pH 6.8?

pH 6.8 mimics the environment of the lower intestine, where many extended-release formulations are designed to release their final dose. If a generic tablet dissolves too quickly at this pH, it releases the drug too early - defeating the purpose of being extended-release. Many formulations fail here because their coatings or matrices don’t hold up under intestinal conditions. This is why testing at all three pH levels (1.2, 4.5, 6.8) is mandatory - it’s not just a formality, it’s a functional test.

Is alcohol testing really necessary for all ER drugs?

Yes, for any extended-release drug containing 250 mg or more of active ingredient. Alcohol can disrupt the polymer coatings or matrix systems that control drug release, causing the entire dose to be released at once - a phenomenon called “dose dumping.” This can lead to dangerous overdoses. Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER painkillers were withdrawn because of this risk. Testing in 40% ethanol is now standard for these products.

Can a generic MR drug pass bioequivalence but still cause problems in patients?

Yes. Bioequivalence tests measure average exposure and peak levels, but they don’t capture subtle timing differences that matter for brain or heart activity. A 2016 study found that 18% of generic extended-release antiepileptic drugs had higher seizure breakthrough rates than the brand - even though they passed all FDA tests. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, like warfarin or lithium, even small delays in release can lead to clinical failure. That’s why tighter acceptance ranges (90-111%) are used for these drugs.

Why do only big companies make generic modified-release drugs?

Because it’s expensive and technically demanding. A single MR bioequivalence study costs $1.2-1.8 million - nearly double the cost of an immediate-release study. You need specialized labs, advanced software, statisticians who understand RSABE, and years of experience. Only large pharma and major contract research organizations (CROs) have the resources. Small biotechs rarely attempt it - less than 3% of MR BE studies are done by them.

Beth Templeton

January 6, 2026 AT 17:40Pavan Vora

January 7, 2026 AT 09:08Gabrielle Panchev

January 8, 2026 AT 16:14Saylor Frye

January 10, 2026 AT 00:20Wesley Pereira

January 10, 2026 AT 08:42Cam Jane

January 11, 2026 AT 03:27Isaac Jules

January 12, 2026 AT 18:31Amy Le

January 14, 2026 AT 06:46Stuart Shield

January 14, 2026 AT 08:31Dana Termini

January 14, 2026 AT 16:16Susan Arlene

January 14, 2026 AT 17:31Indra Triawan

January 15, 2026 AT 04:12Joann Absi

January 16, 2026 AT 04:11Lily Lilyy

January 18, 2026 AT 02:25