Antiemetic Selector for Opioid-Induced Nausea

Select Symptom Type

When someone starts taking opioids for pain, nausea and vomiting often show up uninvited. About one in three patients experience opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV), making it one of the most common reasons people stop their pain medication. It’s not just uncomfortable-it’s a major reason people don’t stick with their treatment. In fact, studies show many patients would rather endure more pain than deal with constant nausea. The good news? There are clear, evidence-backed ways to handle it without adding unnecessary risk.

Why Opioids Make You Nauseous

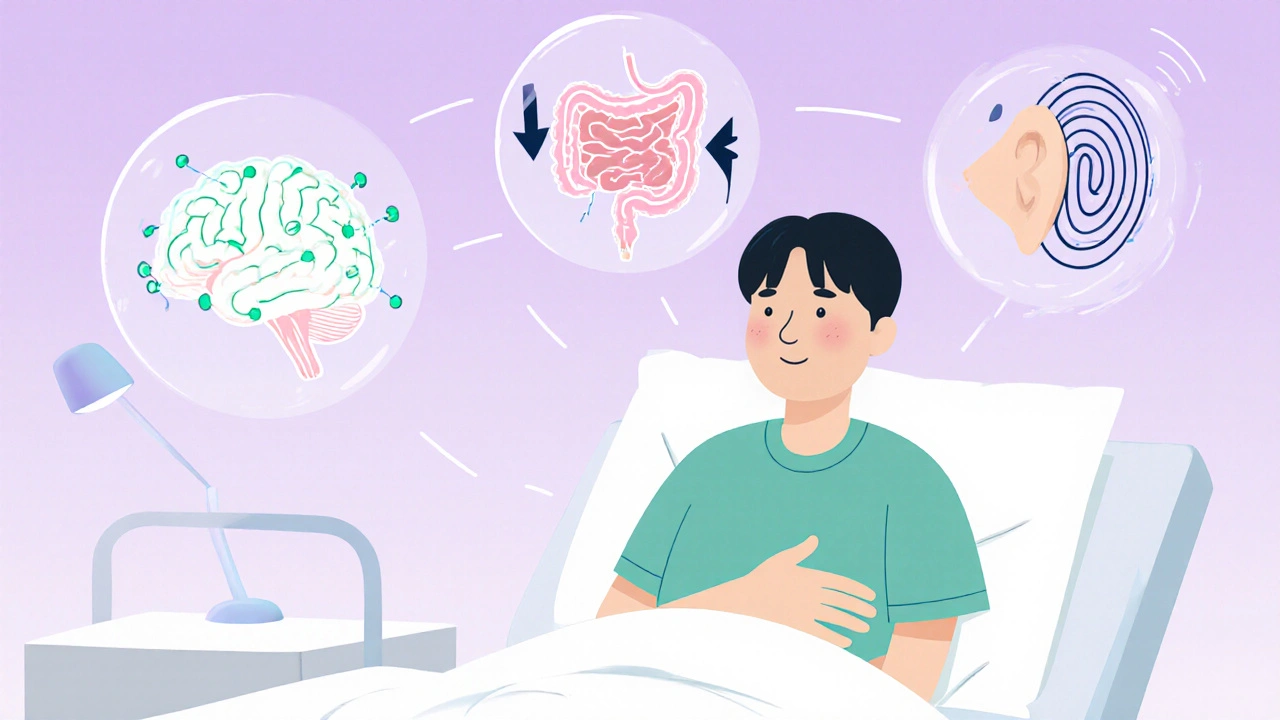

Opioids don’t just block pain signals. They also trigger nausea through multiple pathways in the body. One key mechanism is their effect on the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the brainstem. This area has dopamine receptors, and when opioids bind to them, they send false signals that something is wrong-like food poisoning-leading to vomiting. Opioids also slow down your gut, which increases pressure and triggers nausea through nerve pathways. For some, it’s not the gut at all-it’s the inner ear. Opioids can heighten sensitivity in the vestibular system, making motion or even just standing up feel like spinning.That’s why not all nausea from opioids is the same. One person might feel queasy after eating, another might get dizzy when they stand up. Understanding the root helps pick the right treatment.

Common Antiemetics and How They Work

There are three main classes of antiemetics used for opioid-induced nausea, each targeting a different pathway:- Dopamine antagonists like metoclopramide and droperidol block dopamine receptors in the brain’s trigger zone. These were once the go-to, but newer data shows they’re often ineffective as a preventive measure.

- 5-HT3 antagonists like ondansetron and palonosetron block serotonin released in the gut and brain. They’re more effective for nausea tied to gut irritation or central stimulation. A 2020 study found palonosetron reduced nausea in 42% of patients, compared to 62% with ondansetron.

- Anticholinergics and antihistamines like scopolamine and meclizine work best when nausea is linked to dizziness or motion sensitivity-common in older adults or those with balance issues.

But here’s the catch: some of these drugs carry serious risks. Both droperidol and ondansetron have FDA black box warnings for QTc prolongation-a heart rhythm issue that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. That’s not a risk you take lightly, especially in older patients or those on other heart-affecting medications.

Prophylaxis Doesn’t Work (Most of the Time)

For years, doctors gave antiemetics before opioids, hoping to prevent nausea before it started. But the latest Cochrane review in 2022 analyzed three clinical trials and found metoclopramide didn’t reduce nausea, vomiting, or the need for rescue meds in patients receiving IV opioids. None of the studies showed a meaningful benefit.That’s not to say antiemetics don’t work-they just shouldn’t be given upfront. The evidence points to a smarter approach: wait and treat. If nausea develops, then choose the right antiemetic based on the symptoms. Giving it before the problem arises doesn’t help and might expose patients to unnecessary side effects.

When to Use Which Antiemetic

Choosing the right drug isn’t about guessing. It’s about matching the drug to the likely cause:- Central nausea (dizziness, no food trigger) → Try ondansetron or palonosetron. These work well when the brain’s trigger zone is activated.

- Gut-related nausea (bloating, slow digestion) → Metoclopramide can help here, but only if used after symptoms appear. Avoid it if the patient has heart rhythm issues.

- Motion-triggered nausea (standing up, turning head) → Use scopolamine patches or meclizine. These target the inner ear system directly.

- Severe, persistent nausea with no clear cause → Consider low-dose haloperidol, an antipsychotic that blocks dopamine without the same QTc risk as droperidol.

Don’t just reach for the first antiemetic on the shelf. Ask: Is this patient dizzy? Do they feel bloated? Did the nausea start after standing? The answer guides the treatment.

Non-Drug Strategies That Work

Sometimes, the best solution isn’t another pill. The CDC’s 2022 guidelines emphasize patient education and non-pharmacological tactics:- Start low, go slow → Begin with the lowest effective opioid dose. Many patients tolerate a 5 mg morphine tablet better than a 10 mg one, especially at first.

- Opioid rotation → If nausea sticks around after a week, switching to a different opioid can help. Tapentadol, for example, has a 3-4 times lower risk of nausea than oxycodone per unit of exposure.

- Dose reduction → Sometimes, lowering the opioid dose slightly doesn’t hurt pain control but cuts nausea significantly. It’s not failure-it’s smart management.

- Hydration and small meals → Dehydration and empty stomachs worsen nausea. Sipping water and eating light snacks like crackers can help.

These strategies aren’t just helpful-they’re proven. A study in palliative care showed that patients who got dose adjustments and education were 40% more likely to stay on their opioid regimen than those who just got antiemetics.

Dangerous Interactions to Watch For

Opioids don’t play well with other drugs. Mixing them with certain antidepressants, migraine meds, or even some antibiotics can cause serotonin syndrome-a life-threatening condition marked by agitation, rapid heart rate, high fever, and muscle rigidity. The FDA has updated labels for all opioid prescriptions to warn about this.Also, combining opioids with benzodiazepines or alcohol increases the risk of slowed breathing and death. Patients on multiple medications need a full review before starting opioids. A pharmacist’s input isn’t optional-it’s essential.

How Long Does Nausea Last?

The good news? Most patients develop tolerance to nausea within 3 to 7 days. That’s why antiemetics are often only needed short-term. If someone is on a new opioid, give them 5-7 days before assuming the nausea won’t improve. Don’t keep adding drugs if the body is still adjusting.For older adults or those with chronic pain, tolerance might take longer. But even then, the goal isn’t to eliminate nausea forever-it’s to get through the initial phase safely.

What Providers Should Do

Clinicians have a clear path forward:- Warn patients before starting opioids: “Nausea is common, but temporary. We’ll manage it if it happens.”

- Don’t prescribe antiemetics routinely. Wait for symptoms.

- Choose antiemetics based on symptom type-not convenience.

- Check for drug interactions, especially with antidepressants and heart meds.

- Consider opioid rotation or dose reduction if nausea persists beyond a week.

- Use non-drug strategies first: hydration, small meals, slow titration.

The goal isn’t to avoid opioids. It’s to make them tolerable. When patients can take their pain medication without vomiting, they’re more likely to get better-and stay out of the ER.

What Patients Should Know

If you’re on opioids:- Nausea is common, but not normal forever. It usually fades in a week.

- Don’t take antiemetics unless you’re actually nauseous. Taking them “just in case” can cause side effects without benefit.

- If you feel dizzy when standing, tell your doctor. You might need meclizine, not ondansetron.

- Keep a symptom diary: When does nausea happen? After meals? When you move? This helps your provider choose the right fix.

- Never mix opioids with alcohol, sleeping pills, or anxiety meds without checking with your provider.

It’s not about avoiding pain meds. It’s about using them safely. The right approach turns a frustrating side effect into a manageable part of recovery.

Do all opioids cause nausea equally?

No. Opioids vary significantly in their nausea risk. Oxymorphone has the highest risk-about 60 times higher per dose than oxycodone. Tapentadol has a much lower risk, around 3-4 times lower than oxycodone. Morphine and codeine fall in the middle. Switching opioids can help if nausea persists.

Is ondansetron the best antiemetic for opioid nausea?

It’s effective for many, but not always the best. Ondansetron works well for central nausea and gut-related nausea, but palonosetron is more effective and longer-lasting. However, both carry cardiac risks. For patients with heart conditions, low-dose haloperidol or meclizine might be safer choices.

Should I take an antiemetic before my first opioid dose?

No. Studies show prophylactic antiemetics like metoclopramide don’t prevent nausea. It’s better to wait and treat symptoms only if they appear. Taking them early exposes you to side effects without benefit.

Can I use natural remedies like ginger for opioid nausea?

Ginger has some evidence for motion sickness and chemotherapy nausea, but there’s no strong data supporting its use for opioid-induced nausea. It’s unlikely to hurt, but don’t rely on it as your main treatment. Stick with proven medications if nausea is severe.

How do I know if my nausea is from opioids or something else?

Timing helps. If nausea started within hours of your first opioid dose and you didn’t have it before, it’s likely opioid-related. If you have other symptoms like fever, diarrhea, or abdominal pain, it could be an infection or another issue. Talk to your provider-they can rule out other causes.

Is it safe to take antiemetics long-term with opioids?

Generally, no. Most antiemetics are meant for short-term use. Long-term use of dopamine blockers like metoclopramide can cause movement disorders. Serotonin blockers like ondansetron can affect heart rhythm over time. If nausea lasts beyond two weeks, reevaluate the opioid itself-dose, type, or route may need adjustment.

Jeff Moeller

November 20, 2025 AT 13:38Opioids mess with your brain like a broken radio station-static everywhere. Nausea isn’t a side effect, it’s the system screaming it’s overloaded. You don’t need more drugs to fix it, you need to stop treating symptoms like the problem. The body’s not broken, it’s just signaling it’s being abused.

Bette Rivas

November 21, 2025 AT 10:06Really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve seen so many patients get dumped on ondansetron like it’s a magic pill. The cardiac risks are real, especially in older adults on multiple meds. I always start with non-pharm approaches-small meals, hydration, slow titration. If nausea hits after 3 days, then I match the drug to the symptom. Palonosetron’s great if the heart allows it, but haloperidol 0.5mg is my quiet hero for stubborn cases. And yes, ginger? Cute, but it’s not replacing evidence.

Greg Knight

November 23, 2025 AT 08:56Listen, I’ve been managing chronic pain patients for 18 years. The biggest mistake? Giving antiemetics before nausea even shows up. It’s like putting a raincoat on someone before it clouds over. You’re just adding side effects for zero benefit. I tell my patients: ‘If you feel queasy, tell me. We’ll fix it then.’ Most of them are fine by day 5. And if they’re not? We rotate opioids. Tapentadol’s a game-changer-less nausea, same pain control. Stop overmedicating. Let the body adapt. It’s not weakness, it’s physiology.

rachna jafri

November 23, 2025 AT 15:41They don’t want you to know this but the FDA black box warnings? That’s Big Pharma covering their asses after they pushed these drugs on grandma’s couch for 20 years. Ondansetron? Designed to keep people hooked on opioids so they keep buying. They don’t care if you throw up-they care if you keep paying. And don’t get me started on ‘opioid rotation’-that’s just another way to sell you a new brand-name pill. Real solution? Don’t start the damn opioids in the first place. Natural pain management exists. They just don’t fund it.

Tyrone Luton

November 25, 2025 AT 06:09There’s a deeper truth here: we’ve turned medicine into a menu. Pick your nausea fix like it’s a Starbucks drink. But the body isn’t a vending machine. You don’t get to insert a dollar and get relief. Opioid nausea isn’t a bug-it’s a feature of a system that’s fundamentally toxic to human biology. We’re treating the symptom because we’re too lazy to ask why we’re prescribing opioids at all. Maybe the real question isn’t which antiemetic, but why are we giving opioids to so many people who don’t need them?

Hannah Machiorlete

November 26, 2025 AT 18:16i hate when people act like ginger is some miracle cure for opioid nausea lmao. i had my grandma try it and she just sat there looking confused while puking into a bucket. also why is everyone so obsessed with ondansetron? i had a patient who got it and then started hallucinating because she was on sertraline too. serotonin syndrome is real and nobody talks about it enough. also why do docs always forget that old people get dizzy just from standing up? meclizine is literally the answer for half of them and no one even thinks of it.

Herbert Scheffknecht

November 28, 2025 AT 16:59Let’s be real-this whole system is built on the illusion of control. We want to predict, prevent, and perfect. But biology doesn’t care about our protocols. Nausea isn’t a variable to be eliminated-it’s feedback. It’s your autonomic nervous system saying, ‘This is too much.’ The idea that we should just wait and treat? That’s not a strategy, it’s humility. It’s admitting we don’t have all the answers. And maybe that’s why so many patients drop out-they don’t want a pill for every sensation. They want someone to say, ‘I see you. Let’s adjust.’ Not another algorithm. Not another checklist. Just presence.

darnell hunter

November 30, 2025 AT 02:47The empirical evidence presented is methodologically sound and aligns with contemporary clinical guidelines. Prophylactic administration of antiemetics lacks statistical significance in randomized controlled trials, as corroborated by the 2022 Cochrane review. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic profiles of 5-HT3 antagonists necessitate careful cardiac monitoring due to QTc prolongation risk. It is imperative that clinicians adhere to symptom-targeted interventions rather than empiric prescribing. Non-pharmacological measures, including dose titration and opioid rotation, are evidence-based and underutilized. This document constitutes a clinically responsible framework for opioid-induced nausea management.

Lauren Hale

December 1, 2025 AT 02:34I’ve had patients tell me they’d rather sit in pain than vomit all day. That’s not weakness-that’s survival. We forget that. I don’t hand out antiemetics like candy. I sit with them. I ask: ‘When does it hit? After you eat? When you stand?’ Then I match the tool to the problem. And if it’s still there after a week? We talk about switching opioids. Not adding more pills. Always less. Always slower. And I never, ever start them on anything until they know it’s okay to say, ‘This isn’t working.’ Because the real win isn’t stopping nausea-it’s keeping them on the treatment that lets them live again.